Gender roles have played a significant part in shaping how people view each other and their places in society. Gender stereotypes are often reinforced in young children through the media they consume, particularly in fairy tales and other forms of literature. Even childhood favorites hold a surprising amount of gender bias and toxic messages. In Winnie the Pooh, other than Kanga—the mother figure in the story—every character is male, despite ample opportunity to add diverse female representation. In a popular collection of fairy tales edited by Andrew Lang called The Blue Fairy Book, the amount of misogynistic stereotypes and glorified sexual violence these stories contain is shocking. Traditionally minded individuals argue that gender roles provide people with a roadmap for how they “should” lead a fulfilling life, based solely on anatomy. These individuals may feel that conforming to these roles will allow them to live within society’s comfort zone and feel secure with their life expectations. However, what was once considered conventional is now being questioned as researchers come to terms with the harms of gender stereotypes. The perpetuation of gender stereotypes in children’s literature affects childhood development by attacking youth’s self-esteem, altering their perceptions of the world, and ultimately limiting the freedom to explore their identities.

Gender roles have played a significant part in shaping how people view each other and their places in society. Gender stereotypes are often reinforced in young children through the media they consume, particularly in fairy tales and other forms of literature. Even childhood favorites hold a surprising amount of gender bias and toxic messages. In Winnie the Pooh, other than Kanga—the mother figure in the story—every character is male, despite ample opportunity to add diverse female representation. In a popular collection of fairy tales edited by Andrew Lang called The Blue Fairy Book, the amount of misogynistic stereotypes and glorified sexual violence these stories contain is shocking. Traditionally minded individuals argue that gender roles provide people with a roadmap for how they “should” lead a fulfilling life, based solely on anatomy. These individuals may feel that conforming to these roles will allow them to live within society’s comfort zone and feel secure with their life expectations. However, what was once considered conventional is now being questioned as researchers come to terms with the harms of gender stereotypes. The perpetuation of gender stereotypes in children’s literature affects childhood development by attacking youth’s self-esteem, altering their perceptions of the world, and ultimately limiting the freedom to explore their identities.

Exposure to gender stereotypes in books decreases children’s self-esteem and demands that they observe the unofficial rules society standardizes. Before continuing the conversation, it will be useful to have a general definition of gender stereotypes. Anjali Adukia (2022) and her colleagues explain, “Gender stereotypes are defined as ‘a generalized view or preconception about attributes, or characteristics that are or ought to be possessed by women and men or the roles that are or should be performed by men and women.’”1 It appears that the notion of gender stereotypes came about from societal expectations of conformity that have reigned supreme through the years.

These stereotypes differ between women and men, but both sides remain problematic. Ya-Lun Tsao (2020) quotes M. A. Kramer when she writes, “Female characters are portrayed as more concerned with appearance. Females are depicted as dependent, emotional, silly, clumsy, and lacking intelligence. They are passive, gentle, domestic, motherly, and unassertive.”2 Snow White is a prime example of these traits, with her personality being defined by her beautiful looks and her ability to care for a house of men through her “motherly instincts.” Additionally, Dr. Munejah Khan (2019) considers the damaging nature of gender stereotypes, particularly those relating to toxic masculinity. She quotes Lois Tyson when she states, “Traditional gender roles cast men as rational, strong, protective, and decisive.”3 While Disney’s Gaston was not in the original tale of Beauty and the Beast, few male characters better portray the image of an arrogant, womanizing man whose world revolves around his narcissism. While several of these traits are not necessarily negative, it can become an issue when female characters only possess passive traits while male characters are primarily bestowed with active ones.

When female characters are portrayed with sexist stereotypes, it affects women’s self-esteem by pressuring them to fit within certain expectations. Kennedy Casey (2021) and her colleagues write, “The underrepresentation of female characters in children’s books, and media more generally, has been referred to as ‘symbolic annihilation’ because it is believed to promote the marginalization of women and girls by suggesting that they play a less significant role in society.”4 As unfortunate as it seems, women today still suffer the consequences of sexism and being seen as inferior to men, whether in media or reality.

Fairy tales are especially notorious for pushing women to the side. Khan says that in “Snow White,” “The idea propagated through the tale is perhaps that Snow White is happy to stay at home and perform the chores and the lesson to be drawn from her tale is that women should be passive.”5 There has long been the implication that women are meant to be content as housekeepers while men work to provide for the family, and Snow White’s tale exemplifies this. In “Cinderella,” “The moral of Cinderella’s story can be defined as ‘patience and endurance is rewarded’ thereby women are instructed to suffer in silence with the hope that their patience too will be rewarded.”6 While Cinderella can be a source of comfort to girls who have no control over their current situation and wish only for happiness after enduring their trials, it is one of the many fairy tales that discourage women from taking charge of their lives and finding the strength to be themselves.

While female stereotypes tend to be a considerable issue in children’s literature, male stereotypes can be detrimental as well. Khan quotes Seda Peksen when she writes that boys “are always expected to be the breadwinners, the heroes who never cry, who are never frightened, and who should always take the first step.”7 This is an example of toxic masculinity and the pressure that is put on young boys to “man up” and “stop acting like a girl,” as emotional responses are seen as a negative trait. Conversely, Anna Knyazyan (2017) notes, “In Andersen’s fairy tales the males displayed more emotions than the females. This was too unexpected since females were typically stereotyped as more emotional.”8 Emotions are a double-edged sword for men—they are expected to be the epitome of aggression, courage, and pride, yet feelings such as genuine joy and sorrow are frowned upon.

Disney films also include several examples of themes often found in children’s literature. Knyazyan lists five of these themes: “1. males use physical strength to express their emotions; 2. males are unable to control their sexuality; 3. males are strong and heroic; 4. males always have non-domestic jobs; 5. fat males always have negative characteristics.”9 For example, The Hunchback of Notre Dame’s Claude Frollo embodies the second point by demonstrating alarming sexual harassment towards Esmeralda throughout the duration of the film. Additionally, the fourth point relates to the Sultan in Aladdin when he expects Jasmine’s future husband to be responsible for ruling Agrabah while his daughter takes on a more docile role. These examples may seem like normal occurrences in most stories, but they reflect real-world issues that imply that children who do not live up to these standards are worthless and need to “fix” themselves to be happy.

Without discussing the controversy surrounding them, gender stereotypes can lead children to develop unhealthy biases concerning world issues. In many literary works, gender roles have been used to reinforce stereotypes that place strict expectations on men and discourage women from achieving their true potential. Ria Chinchankar (2015) uses William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet as an example of gender limitations when she says, “Romeo is instructed to stand up and be a man and to stop acting like a woman when he becomes overly emotional upon hearing news of his banishment. We still say stuff like this today.”10 Boys are taught from a young age that crying is a sign of weakness while women are seen as overly emotional. Defining emotional expression as a strictly feminine attribute further alienates the male and female genders from each other.

Women have often been perceived as being “less” than men throughout history. In her speech, Chinchankar references women's roles during the time Shakespeare lived. She says, “Women were barred from university, seen as a distraction to men. This meant the women were unable to get higher paying, more qualified jobs. Over time, they began to believe that they themselves weren’t as capable as men.”11 It is only in recent decades that women have begun to attain basic human rights, such as the ability to receive higher education, become homeowners, and act as government representatives. These rights were only achieved after centuries of fighting back against harmful attitudes towards womanhood. Unfortunately, “gender stereotypes persist in society,”12and “implicit attitudes about females being submissive and less worthy than males remain pervasive.”13 Progress towards reducing these stereotypes has been slowed as children are taught to believe that women have less value than men, causing them to develop negative perspectives concerning gender and lose sight of the potential of others.

Another devastating but relevant truth about gender stereotypes is how they normalize sexual harassment and assault. With dangerous attitudes such as “boys will be boys” or “women are responsible for men’s actions,” ideas about sexual harassment can form at an age long before children are aware of their impact. Leah Shafer (2018) writes, “Stubborn beliefs cultivated from an early age such as ‘girls are bad at math,’ ‘girls are better at cooking,’ or ‘boys don’t cry,’” lead to “disturbing truths about the frequency of sexual harassment.”14 Not only do messages about what boys and girls can and cannot do limit their self-esteem and potential, but they also indirectly suggest that women must submit to men in every circumstance. The original “Sleeping Beauty” has long been known for its problematic origins where “The princess in the whole tale is portrayed as an object of male gaze and has absolutely no opinion to express.”15 A wandering prince taking advantage of a slumbering princess has left many readers horrified by its inclusion in a children’s story, despite this issue still occurring frequently in modern society. If youth were more educated on these stereotypes and their hidden implications, perhaps the tragedy of sexual assault would become less of a problem in the world.

Gender stereotypes also contribute to negative attitudes about mental health. While mental health is a widespread issue with many nuances, mental illness in men tends to be much less recognized than in women due to the expectation for them to be “always portraying a tough exterior.”16 Men’s mental health is put at risk when they are “unable to reach out for support or seek a therapist, and helps explain why the suicide rate for males is two times higher than the suicide rate for females. This idea that they're not meant to love can be fatal.”17 Men are mocked for both asking for help and expressing vulnerable emotions, so it is no wonder so many incredible men have been lost due to the stigmas placed on mental illness.

While men are pressured to approach life with stoicism, women are often faced with countless opinions arguing that they can never truly be happy without the opportunity to marry a Prince Charming and settle down to raise a family. It is unfortunate how “often the plot of fairy tales is how a girl is rescued from misery by prince charming, the implication being that marriage to the right man guarantees happiness and assures the ‘they lived happily ever after’ ending to a girl’s story.”18 While women who choose to marry and raise children should be highly respected, not everyone is content with this path. Some women might never want to get married, instead finding happiness in traveling or pursuing their careers. Some women may desire to get married but never find the right person. Multiple women would prefer to spend the rest of their lives with a “princess” or otherwise than a “prince.” Some women may be unable to bear children, prefer to adopt, or may not want children at all. All of these choices are equally valid, and a woman’s self-image and happiness should not rest on whether or not she falls in love with a man.

The expectations that gender stereotypes set in children’s literature limit the freedom of youth to explore their identities. Even from a young age, children are discouraged from exploring non-traditional gender roles. Parents will likely give their daughters dolls to explore motherhood while their sons receive “toys for boys,” like model cars and action figures. Society tends to “view gender identity as the process through which children acquire the characteristics, attitudes, values and behaviors that society defines as appropriate to their gender and which lead them to adopt roles and responsibilities that are prescribed to men and women.”19 Even in literature, these concepts of “correct” gender identity are suggested through the traits and behaviors of the characters.

Children’s books are biased due to the way genders are depicted in stories and illustrations. Readers of youth literature will notice that “in most children’s picture books, males characteristically dominate titles, pictures, and texts. Female characters, on the other hand, are not only under-represented in titles and central roles but also appear unimportant.”20Not only are children taught ideas such as “girls cannot hold leadership positions” or “boys can never appear soft,” but their books also include messages of one gender holding superiority over another. Children may also develop a fear of judgment over whether their interests align with traditional gender norms. They are lost in the message that women must do the housework while men hold the main source of income. However, people may take comfort in the fact that “children who were read non-sexist stories…reduced their notions of gender-role stereotypes” and “developed fewer stereotypical attitudes…after being read stories about people who fought gender discrimination.”21Children are generally more accepting and open to various concepts at a young age, so the earlier they learn to take a stand against gender stereotypes, the more likely it is that they develop a celebration of positive ideas about gender.

Many children’s preferences are influenced by the media they consume. Often, children will prefer to read books with a main character whose gender is the same as their own. Kirsten Heuring (2021) writes, “Girls are more likely to have books read to them that include female protagonists than boys…Children are more likely to learn about the gender biases of their own gender than of other genders.”22 By reading books that focus solely on their own gender, children are being exposed to the stereotypes of how they “should” behave rather than exploring stories from other perspectives. This issue particularly resonates with women, especially when only one kind of female character is present. Whether they be a damsel in distress or a tomboy, these stereotypes “prevent female human potential from being realized by depriving girls of a range of strong, alternative role models.”23 The harmful stereotype of women only being useful in domestic roles is prevalent in classic literature, but modern media has popularized the “strong, female character” trope. What authors and readers must understand is that women do not have to possess stereotypical male traits to be seen as “strong.” There is power to be found in diverse female personalities, whether the woman wields a sword in battle or heals wounded soldiers.

As this discussion of gender stereotypes ends, one might ask: is there anything that can be done to mend the scars these ancient traditions have left upon the world? The answer is yes, although it will take dedication to establish a change of heart. The most straightforward solution is to examine personal biases and any preconceived notions about gender roles. People can “change [their] own actions. Are you a man who’s always dreamt of dancing ballet? Go ahead and do it. Shed the restrictions our culture places on people.”24 A person should never be too scared to pursue their dreams simply because society told them their desires are unorthodox. The world would be much less interesting if everyone pursued the same path in life.

Parents can play a significant part in teaching their children about gender bias. They can “talk to kids about the stereotypes they encounter at school, on television, or while shopping…Explain to kids how stereotypes can be so ingrained in our society that we don’t always notice them.”25 The only reason children grow up accepting the normality of gender stereotypes is because they have never been taught that there is anything wrong with them in the first place. Parents can also “Encourage boys to talk about their feelings and worries, and praise them for expressing empathy and care,” as well as “Make it clear to girls that they can and should be leaders.”26 These tips do not have to be exclusive to one gender over another, but some counsel may be more relevant to certain genders depending on their situations in life. There are countless other examples of how individuals can lessen gender bias in the world; what is important to note is that action can be taken and that society does not need to continue existing in a cycle of conformity.

Without attempting to reduce harmful gender stereotypes in children’s literature and provide education on their impact, youth will lose the opportunity to have a healthy relationship with gender. Children do not need to bid farewell to classic stories simply because gender stereotypes exist within their pages—on the contrary, there are many important life lessons to be gained from these tales. Instead, parents and teachers should attempt to educate children on approaching gender stereotypes with an open mind. If negative depictions of gender stereotypes persist in modern literature, youth may remain trapped in a pattern of destructive gender biases and mixed messages about their roles in life. Girls will never be able to see themselves as superheroes dashing through the air to save citizens from a falling building, and boys will never be able to hold a tea party in the garden with their friends for fear of being seen as “not manly enough.” Authors, parents, and any other adults who play a part in childhood development need to take the necessary steps to promote positive representations of gender inclusivity in books and help children who feel lost in the world of gender stereotypes to find themselves through stories.

The place where my curiosity struggles the most in educational environments has always been during English class. Despite the misleading name, “English class” has not been about teaching the mechanics of English since I was in middle school. I want to learn about English in English class, but I don’t.

And I don’t just love English. I love languages as a whole. I love the way they work, I love thinking about how words came to be, and I love grammar rules. I want to learn how different languages handle forms of “to be”; how they handle past perfect, imperfect, and pluperfect tenses; and how a language handles clusivity in its pronouns. Since that seems to be a tall order for a high school English class, I have had to take matters into my own hands.

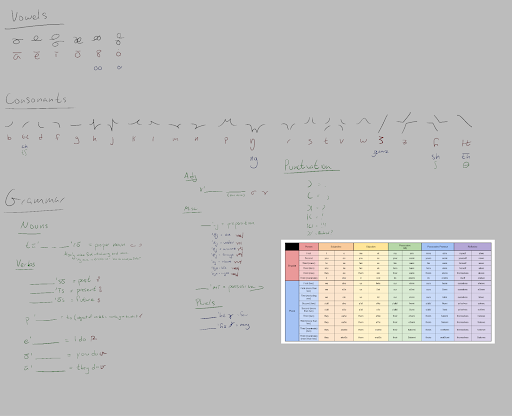

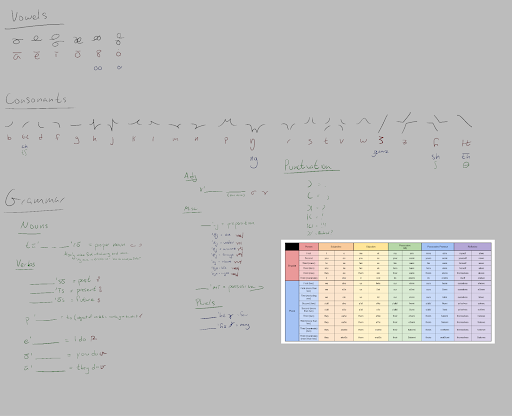

I have spent a significant portion of my free time over the past few years creating secret codes and rudimentary replacement ciphers parading as other languages. This past year I’ve set my sights on a more difficult challenge: inventing an entirely new language myself. I’m currently working on making a constructed language, or a Conlang, that is meant to be used in a fictional world. It has a basic grammar system and structure and an in-progress dictionary of over 200 words. The image I’ve attached with my essay shows my language’s alphabet.

Curiosity is a powerful thing, but it is often stifled by school curricula. As English class has become less about learning English and more about writing essays and reading literature, this has become even truer for me. While those aspects of English class have value, there also needs to be an understanding of grammar, punctuation, spelling, syntax, and a healthy respect for the Oxford comma.

Thank you, e’heponis.

What does it mean to be asexual? While often misunderstood, asexuality is a valid and multifaceted identity within the LGBTQIA+ community. This is often confused with the closely related aromantic label, where an individual feels little to no romantic attraction. Many people believe love cannot exist without sex and that romantic and sexual attraction must always be intertwined. However, as someone who identifies on the asexual, or “ace,” spectrum myself, I’ve found that there are many ways to experience love, whether it be romantic, platonic, familial, or otherwise.

What does it mean to be asexual? While often misunderstood, asexuality is a valid and multifaceted identity within the LGBTQIA+ community. This is often confused with the closely related aromantic label, where an individual feels little to no romantic attraction. Many people believe love cannot exist without sex and that romantic and sexual attraction must always be intertwined. However, as someone who identifies on the asexual, or “ace,” spectrum myself, I’ve found that there are many ways to experience love, whether it be romantic, platonic, familial, or otherwise.

Looking back, I now realize how my religious upbringing shaped my early understanding of attraction and relationships. Purity culture is a key principle in my religion’s teachings, and I was taught to view physical desires as both sacred and unclean. Because I had never felt sexual attraction, the constant admonitions from church leaders to “remain virtuous” never seemed difficult to follow.

“This will be easy,” I thought. “I’ve never felt that way about anybody!”

If only I could travel back in time and tell my teenage self what I know now.

I first encountered the term “asexual” as a human sexuality when a young author I admire, Lancali, openly discussed her identity. At first, I was unsure of what the label meant and assumed it couldn’t possibly apply to me. I thought romantic and sexual attraction was the same thing, and although I squirmed at the idea of what was expected to happen on a wedding night, I still had a strong desire to be in a romantic relationship.

It wasn’t until after I read Alice Oseman’s Loveless that I started to understand the word “asexual’s” meaning. The book follows Georgia Warr, a college Freshman navigating her newfound aromantic asexual, or “aroace,” identity as she learns to value platonic relationships as much as romantic ones. As Oseman is aroace themself, their personal experience helped them create a relatable protagonist who positively represented their orientation.

Reading Loveless right after high school felt incredibly timely, as I was beginning to reflect on my own identity and what awaited me in university life. Through Loveless, not only was I able to get a glimpse into what college is like for young adults, but I also solidified my confidence in my asexuality while reading about Georgia’s joys and struggles.

I was relieved to learn that there are other people who experience love in a nontraditional sense, but it could be isolating at times to watch couples getting married and raising children in a way I wouldn’t necessarily have or want. I still dreamed of having a supportive partner to go on bookstore dates with and talk to about all my joys and challenges in life, but I knew I would never have the same kind of relationship allosexuals—a term for people who aren’t asexual—considered normal. Would I ever find people like me outside of internet forums? Would I ever meet someone who loved every part of me, asexuality and all?

Amid my anxiety, I developed a support group that made accepting myself much easier. When I came out to my best friend, she told me she had already done plenty of research on asexuality on her journey toward discovering she was bisexual. I found out that someone else I’m close with is also on the ace spectrum, and I was ecstatic to find a person I knew in real life who had similar experiences to me whom I could relate to.

As time went on, I learned about microlabels and the nuanced beauty that is the asexual spectrum, whether an individual be sex-repulsed, sex-neutral, sex-positive, or another label they prefer. I also discovered two other labels that fall under the ace spectrum: graysexuality and demisexuality. A graysexual individual only feels sexual attraction occasionally or to a low degree, and a demisexual person needs to form a strong emotional bond with their partner before feeling any kind of sexual attraction.

I learned to value the fluidity of sexuality, understanding it would be normal for my perception of my orientation to evolve throughout my life. As I’m not aromantic, I’ve gone back and forth between identifying as bisexual and lesbian, which can be a confusing process. Labels may be a source of comfort for many, but there are no rules saying anyone needs to put themselves in a box and explain every detail of their identity to everyone who asks. As a quote from Benj Pasek and Justin Paul’s musical, Dear Evan Hansen, says, “Today at least you’re you, and that’s enough.”

I still face many challenges in a world where sex is prioritized above emotional intimacy, and I often find myself arguing with others about the validity of my orientation. Despite all of this, I’ve found peace in the asexual community. By sharing my experiences and writing ace-spec characters in my future novels, I hope to increase awareness and representation for those who, like me, may have struggled to find themselves in mainstream narratives. Society’s strict expectations for relationships cannot limit the many ways humans feel love.

Honors Submission Essay

My curiosity has not only survived formal education but has become the foundation of my love for space and all it contains. Curiosity for the cosmos has been my constant companion and propels me toward my dream of someday working as an astronaut for NASA.

My love for the universe came with the desire to understand its mysteries, and though I now study physics in college, I have been a student of the stars since childhood. I excelled in school, hungry for deeper meaning behind every lesson, but was often shunned for asking too many questions–especially in our unit on the solar system. So, I began seeking answers myself. I recorded and observed like the astrophysicist I aspired to be. Through stargazing, I made astronomical observations whenever the heavens were observable. I used books to memorize the constellations, charting them to catch any mistakes. For years I was limited to what I could see with the naked eye–until I got a telescope. The world around me grew ever smaller while my view of the universe transcended beyond what I, as a child, thought possible.

Einstein claimed, “It is a miracle that curiosity survives formal education”, and I certainly agree. School proved to be a place of rigid conformity, punishing my curiosity rather than fostering it. Though my curiosity was at times stifled, it has never been extinguished. Driven by the same compulsions that drove Magellan and Shackleton, I am called to the darkness, the dangers, the strange, and the weird. Space exploration is the very manifestation of human curiosity and determination. I strive to be among the astronauts to take the leap, steering humanity to Mars and beyond, a milestone that will forever alter our understanding of what's possible. I will do this not only to satisfy my curiosity but to inspire future generations who find themselves, like me, unsatisfied just looking at the stars.

But before I reach any moons, I will continue to take “small steps for man” here on Earth. While space is our future, the Earth is our present.

In a letter written to his younger sister on March 30th, 1772, Benjamin Franklin mentions, "She has shown me some of her Work which appears extraordinary. I shall recommend her among my Friends if she chuses to work here."¹ This woman mentioned in Benjamin Franklin's letter can be identified as Patience Lovell Wright, or Mrs. Wright, as Franklin commonly called her. The "extraordinary" work that Franklin refers to just so happens to be Wright's collection of wax sculptures of well-known political figures. These sculptures are why Patience Wright is recognized as America's first and one of its finest sculptors.² During her life, Wright proved herself instrumental in building the new nation through the artistic traditions she developed and through her support of the revolutionary cause.

In a letter written to his younger sister on March 30th, 1772, Benjamin Franklin mentions, "She has shown me some of her Work which appears extraordinary. I shall recommend her among my Friends if she chuses to work here."1 This woman mentioned in Benjamin Franklin's letter can be identified as Patience Lovell Wright, or Mrs. Wright, as Franklin commonly called her. The "extraordinary" work that Franklin refers to just so happens to be Wright's collection of wax sculptures of well-known political figures. These sculptures are why Patience Wright is recognized as America's first and one of its finest sculptors.2 During her life, Wright proved herself instrumental in building the new nation through the artistic traditions she developed and through her support of the revolutionary cause.

In 1725, Patience Wright was born in New Jersey to Quaker parents. She spent her childhood in Bordentown and Long Island and married Bordentown resident Joseph Wright in 1748, soon having between three and five children with him. Not much is recorded or known about her life before her marriage, and questions thus arise about where her sculpting skills came from. There would have been no examples of sculptures nor sculpting instructors in the small Quaker colony, meaning Wright was likely self-taught. While her artistic development is often debated, some scholars believe she learned the trade by sculpting faces in clay and bread dough. Regardless of her training, she began to gain a positive reputation for the likeness she could capture in her wax figurines.

When Wright’s husband passed away in 1769, she had to figure out how to live as a widowed mother. To make a living, she looked towards her sculpting skills. Accounts claim that “[Wright]… showed a decided aptitude for modelling, using dough, putty, or any other pliable material she could find, and being left by her husband with scant means, made herself known by her small portraits in wax.”3 Not only was wax a more affordable option for sculpting, but its malleability and translucent nature made it perfect for replicating the details and capturing the likeness of the models. Wright took the nature of this medium and used it to her advantage, traveling around the East Coast to fulfill portrait commissions before eventually settling in New York.4 There, she continued to fill commissions and sculpt for lesser-known political figures, such as her wax and wood profile bust of the American Admiral Richard Howe (fig. 1).

In 1771, a fire melted and destroyed many of Wright’s works, and she looked towards Europe for a new start. In Europe, wax sculptures were gaining popularity as the public found fascination and curiosity with the illusionistic nature of the medium. Not only was the popularity of wax spreading, but many female artists were finding success sculpting with it.5 Wright took the knowledge and skill she had built in the United States and, in 1772, made her way to London with her children. In England, Wright capitalized on the popularity of wax figures that was not entirely present in the United States. She sculpted British subjects and created full-body sculptures, life-size busts, and smaller profile busts, all from wax. She began to pick up acclaim, which is evident when Dunlap mentions that “There is ample testimony in the English periodicals of the time, that her work was considered an extraordinary kind; and her talent for observation and conversation… gained her the attention and friendship of many distinguished men of the day.”6 In her first year in London, Wright began sculpting for Jane Mecom, the sister of Benjamin Franklin, who lived in Europe at the time. It was then that Wright started gaining recognition from important political figures in the United States, as is evident by her “extraordinary” talent, voiced by Franklin in his previously mentioned letter.7

While in England, Wright not only started gaining widespread popularity among American audiences, but she also began developing a fervor for the revolutionary cause occurring in the colonies. Toward the beginning of her time in London, Wright had built a good relationship with King George III of England and his wife Charlotte, even having them sit for her. However, as the revolution went on, she began to lose trust in them. She was said to have believed “that the king was personally responsible for the war and that the institution of monarchy was politically unjust.”8 She continued to work for the British population. Still, as she sculpted them, she would listen closely to their discussions of political gossip and military matters. Wright would then pass this information to American correspondents, warning of British military plans and encouraging the colonies to stand firm.9 These messages were primarily passed through letters, but some argue that Wright even hid warnings in the wax sculptures that were shipped to the colonies. While the exact benefit of her warnings has not been identified, it is assumed that they gave some aid in making preparations for the revolutionary troops.

While contributing to the revolutionary cause, Wright continued to gain acclaim for her sculptures while in England. She fulfilled American and British commissions, creating images of well-known political and diplomatic figures. While few of her works from this time have survived, her style and skill can still be seen in her profile bust of Benjamin Franklin, which was created in 1775, and her full-body wax sculpture of England’s Prime Minister, William Pitt, created between 1775 and 1778 (fig. 2 and fig. 3). As Wright continued to sculpt, audiences showed increasing fascination with her unique and realistic creations. This fascination can be seen in the print titled Patient Lovell Wright, created at the height of Wright’s popularity in 1775 by an unknown artist (fig. 4). It depicts Wright holding a male figure who appears to be relatively lifeless. Upon looking closer, viewers can realize that the figure is one of Wright’s Wax creations, but it appears so realistic that it is challenging to determine whether or not it is an actual person.10 This print provides a clear example of how the public was impressed and transfixed by the illusions that Wright created through her waxwork.

Despite the acclaim that Wright had gained in London, it was challenging for her to reside there as a supporter of the newly formed United States. Because of this conflict, she temporarily moved to Paris in 1781, where she likely spent time building a new client base and further developing her sculpting skills.11 After some time away, she returned to England in 1783 and continued painting British subjects. During this time, she also began connecting with George Washington, corresponding with him in letters and sculpting a profile bust of him from between 1784 and 1786 (fig. 5). In these letters, Wright expresses her hope to come back to the United States, telling Washington, “… it has been for some time the Wish and desire of my heart to moddel a Likeness of generel Washington… and Return in Peace to Enjoy my Native Country.”12 While Wright was grateful for the work that she accomplished in England, she longed to return to the United States, where she had not been since she had moved eleven years before. Months later, Washington responded to Wright’s letter, acknowledging her sentiments and praising her work. In his response, he remarks, “… and if your inclination to return to this Country should overcome other considerations, you will, no doubt, meet a welcome reception from your numerous friends: among whom, I should be proud to see a person so universally celebrated.”13 Through these words, it is clear that even Washington, one of the most celebrated men in American history, praised Wright’s work and hoped to see her return to the country, showing the wideness of her reach.

Unfortunately, while Wright hoped to return to the United States, she suffered a fall in 1786 and passed away soon after.14 Although she could not return to the United States, she was still able to make a lasting impact on the American art world. As the new country developed, Americans sought to create a new art vocabulary to define their nation. Patience Wright was able to help with the development of this artistic vocabulary, opening the door to the unique medium of wax and creating realistic sculptures that documented the new nation’s most important political leaders. Her impressive sculptural techniques would be looked upon for generations to come as examples of artistic genius. As long as American sculpture continues to exist, Patience Wright’s legacy and her role in sculpting the nation’s art will live on.

Honors Submission Essay

I walk down the street, marveling at the complexity of the city around me. New Orleans is an incandescently beautiful city. It is home to varieties of music, dance, literature, and art that encompass the melting pot of a city in one enormous hug. On every street corner I walk by I find musicians playing jazz music or artists selling their work. I take photos of it all.

I round a corner and run into a small library. I stop for a breath and marvel at the countless works displayed on the shelves. The shopkeeper smiles at me from the window and beckons me inside, but I stand contently on the outside of the shop reading the multitudes of titles the books throw at my face.

Books are like that, you know.

They suck you into imaginary worlds crafted from the delicately alluring mind of a stranger somewhere in the world. They take you places you never even dreamed of and allow you to form connections with the most unique of characters who seem to become real, if only in the darkest corner of your mind. Books are adventure. They are a deep breath after being submerged in the chaos of everyday life.

With a small wave at the shopkeeper, I walk down the rest of the block, thinking about the multitudes of worlds I have traveled to in my mind.

— One Year Later —

New Orleans. Destroyed. Only the lucky survived.

I trudge down the once-bustling streets, looking for opportunities to help others and freeze.

There.

Right there once stood a library full of stories, now lying in ruin. In rubble. I snap a picture and a sharp pang of grief pierces my soul for the loss of art. The world needs to know that without literature, we are lost.

Chris Jordan, In Katrina’s Wake. Princeton Architectural Press, 2006.

Breath, a basic life function, holds an interesting place in popular culture, regarded in equal parts with romanticism and disdain. One may take a refreshing breath of sweet spring air in joyous recognition of the wonders and beauty of life and nature. Or, one can waste a life away doing little more than breathing. As Tennyson puts it, “How dull it is to pause, to make an end, to rust unburnished, not to shine in use! As though to breathe were life!”1 Regardless of such popular notions of breath, the activity, if it can be called such, is a crucial part of proper singing. As pedagogue Julia Davids and psychologist Stephen LaTour note, “breathing is the foundation of singing.”2 Without a properly drawn and expelled breath, one cannot sing with proper phonation, resonance, or vitality. In order to sing well, then, it is important to know how to breathe well. Despite its importance, or perhaps because of it, there is a wide range of opinions on the proper ways to breathe within the context of singing. In regard to exhalation, for example, some, such as Richard Miller, favour the Italian appoggio technique.3 Others favor a contraction of the abdomen, or an outward distention, or even that the singer does little at all to retain or push out the air.4 With so many differences of opinion from a variety of reputable sources, one might wonder which technique is most effective in the process of producing good singing. This paper will attempt to examine the benefits and drawbacks of the variety of opinions in literature, in order to find the most optimal method of breathing.

Breath, a basic life function, holds an interesting place in popular culture, regarded in equal parts with romanticism and disdain. One may take a refreshing breath of sweet spring air in joyous recognition of the wonders and beauty of life and nature. Or, one can waste a life away doing little more than breathing. As Tennyson puts it, “How dull it is to pause, to make an end, to rust unburnished, not to shine in use! As though to breathe were life!”1 Regardless of such popular notions of breath, the activity, if it can be called such, is a crucial part of proper singing. As pedagogue Julia Davids and psychologist Stephen LaTour note, “breathing is the foundation of singing.”2 Without a properly drawn and expelled breath, one cannot sing with proper phonation, resonance, or vitality. In order to sing well, then, it is important to know how to breathe well. Despite its importance, or perhaps because of it, there is a wide range of opinions on the proper ways to breathe within the context of singing. In regard to exhalation, for example, some, such as Richard Miller, favour the Italian appoggio technique.3 Others favor a contraction of the abdomen, or an outward distention, or even that the singer does little at all to retain or push out the air.4 With so many differences of opinion from a variety of reputable sources, one might wonder which technique is most effective in the process of producing good singing. This paper will attempt to examine the benefits and drawbacks of the variety of opinions in literature, in order to find the most optimal method of breathing.

Posture

If good breath is the foundation of good singing, good posture is the foundation of good breath. As Davids and LaTour note, “correct [singing] posture elevates the ribs, allowing greater lung expansion and finer control of breathing.”5 Elevating the ribs through correct posture does two things. First, it permits the ribs to expand more fully during inhalation, allowing for a deeper breath. Second, by elevating the ribs, the abdomen is able to expand further, also allowing for a deeper breath. There are other benefits to correct posture. Again from Davids and LaTour,

without proper posture, muscles that can affect vocal production must compensate to maintain body position. Tensing of the muscles [particularly those muscles that compensate to maintain body position] degrades sound quality. Moreover, singers with poor posture tire easily because they spend too much energy on maintaining balance.6

Posture’s importance, then, for breathing and singing is quite substantial, allowing both a full breath and a relaxed musculature. Both the full breath and relaxed muscles mean that the singer tires less quickly, both because of the lower frequency of breaths requiring less work in inspiration and because of the removal of excessively tense muscles.

Not all the literature agrees on the crucial importance of good posture, however. Vennard argues that “it is easy to overemphasize posture … Opera singers demonstrate continually that there is no one posture that is the sine qua non of good singing.”7 In many ways, Vennard is correct in this assessment. While onstage, opera singers are often moving in ways that are not entirely conducive to “proper posture.” In fact, they are required to do so in order to operate at the top levels of opera performance, bending at the waist, standing on the balls of their toes, sitting, laying down, moving about wildly. This being said, however, such movement is rarely so exaggerated that the singer substantially diminishes their ability to fully expand the lungs or tense muscles that diminish vocal quality. In fact, movement that does such things is actively discouraged by many directors. If an opera requires exaggerated movement that diminishes breathing ability, these things are often done when singers are not actively singing.8

If good posture is such an important element of good breath, and therefore good singing, how does one achieve good posture? Feet should be spread a shoulder’s width apart, directly underneath the pelvis. Some argue that one foot should be slightly in front of the other to eliminate the tendency to sway side to side.9 This is perhaps an overly simplistic solution to an issue that could be solved through better acting during singing, if it is indeed a problem at all. After all, if one has one foot too far ahead of the other, it may lead to tensing of those same muscles that poor posture tenses, leading to an inferior vocal production. Some, such as Davids and LaTour, argue for even weight placement across the whole foot, favouring neither ball nor heel.10 Others, such as Marilee David, argue that one should place more weight on the balls of the feet.11 The great benefit of placing more weight on the balls of one’s feet is there will be less of a tendency to lock the knees, so this may be more advisable, particularly for new singers. But the question of weight distribution is perhaps not so important an issue.

Moving up the body from the feet, one should have a straight back such that the hips, chest, and head are all in a straight line.12 The sternum should be elevated, but not exaggeratedly so. All this will work in unison to ensure that the weight of the body is being directed perpendicular to the floor, allowing the legs and spine to bear the weight of the body, rather than abdominal, back, and neck muscles. The shoulders should be back, but not forced so. To simplify all these steps, Vennard compares this posture to “a marionette, hanging from strings, one attached to the top of your head and one attached to the top of your breast bone.”13 This is a very effective visualization, one commonly used in theatre as well as classical singing; though it may at times be easy to forget the second imaginary string attached to the breast bone, leaving a less elevated sternum and more forward shoulders.

As David notes, however, “posture is highly individual.”14 While the physiognomy of the human race is largely the same, there are minor variations that will result in good posture looking slightly different from one person to another. The important principle to remember is that one should have space to fully expand both the abdomen and rib cage during inhalation, while not being so rigid in the effort of maintaining good posture that the muscles are tensed in a way that inhibits quality vocal production. Once one has created a good posture which feels open and comfortable, it is time to look toward the act of breathing itself–in particular, the inhalation.

The Anatomy of Inhalation

As the late Baroque singer and teacher Gasparo Pacchierotti noted, “chi sa ben respirare e sillibare sapra ben cantare” (translated, “he who knows how to breathe and pronounce well knows how to sing well”).15,16 While the subject of good pronunciation is beyond the scope of this paper, it is easy to understand why good breathing is crucial for good singing. In order to vibrate and generate pitch, the vocal folds require air to move between them. The principal anatomical mechanism by which air enters and leaves the body is the breath. A poor breath will generate pitch less effectively than a good breath. Therefore, one must breathe well to sing well. To learn how to breathe well, one must turn to the anatomy which allows one to breathe.

Air, the oxygen which allows every cell within the body to remove certain waste products, is stored in the lungs upon inhalation, where most of it remains before being released from the body during exhalation. The lungs, however, do not control their own expansion; they have no muscular tissue by which to achieve this. The lungs must therefore rely on other parts of the body to expand for it: the inspiratory muscles. Of the many muscles involved in the process of inhalation, the two primary muscles are the diaphragm and the external intercostals. The diaphragm is a dome-like muscle inside of the ribcage which, when contracted, moves slightly downward at the top of its “dome.” The external intercostals are the muscles on the outside of the ribcage, in between each rib, which, when contracted, move each rib outward, similar to a balloon being inflated.17

These inspiratory muscles, which are connected to the lungs, allow the lungs to expand. Through the principle of Boyle’s Law, which states that gases and liquids from an area of high pressure will want to move toward an area of low pressure if possible until there is no difference in pressure between the two areas, air enters the now expanded lungs. With this basic anatomical understanding, it is appropriate to turn to how one feels their inhalation as they sing.

The Process of Inhalation

Most pedagogues note three different types of breathing: clavicular, abdominal, and costal.18 It is largely agreed that the first of these, clavicular breathing, is the sort of breathing that primarily moves the upper part of the chest, near the shoulders and clavicles. Vennard refers to this sort of breathing as “the kind of breathing used by the exhausted athlete, the person who is ‘out of breath.’ It is the ‘last resort,’ desperate breathing.”19 Singers should treat this sort of breathing as the last resort. The primary issues which come from clavicular are an insufficient breath – the upper lungs have a much lower capacity than the lower lungs – and little control over the exhalation.20 David also notes that such breathing creates tension in the throat – a major issue for singing.21

Abdominal breathing is perhaps the most noticeable of the three breathing types. This type of breathing primarily relies on the action of the diaphragm. When the diaphragm contracts to expand and fill the lungs, this expansion pushes the internal organs beneath it further down. Because there is no room for the internal organs to move directly downward, they instead push against the abdominal wall which moves outward to compensate, leading to the outward appearance of a substantially expanded stomach.22 This expansion is advisable, though difficult for a young singer to achieve. Perhaps this is due to societal expectations of thinness, which the expansion of the stomach goes against directly, discouraging people from expanding the abdomen in a natural way to avoid the appearance of being large. To help singers achieve this expansion, David notes, “a full length mirror and the student’s hands are the best tools available.”23 Students can observe their own breathing visually with the mirror and should notice the expansion of the abdomen as they inhale. The hands may also be placed on the abdomen, one near the navel and the other on the natural waist, to feel the abdomen expand. Students may also observe their abdominal breathing by lying on the ground and inhaling. Vennard recommends supplementing this by placing a moderately heavy object on the abdomen and giving the student the goal of raising the object with each inhale and lowering it with each exhale.24

Of the types of breathing, costal breathing is perhaps the least noticeable, but it is nonetheless highly useful for the singer. David argues for a fourth type of breathing, costal-abdominal, which relies on both costal and abdominal breathing and is the most effective type of breathing for singing.25 Costal breathing relies on the external intercostal muscles. The expansion of the space between the ribs allows for a fuller space into which the lungs can expand, and thus, more air which one can control upon exhalation. This sort of breathing is closely related to abdominal breathing: As David notes, “some rib expansion is inevitable with diaphragm contraction [inhalation from abdominal breathing].” That being said, David notes that further expansion is advisable, saying that one can help their students achieve this by instructing them to fill up an imaginary inner tube in their abdomen at the waist.26

Not all teachers agree that costo-abdominal breathing is the ideal. Many have historically believed “the rib muscles should only be used to expand the ribs and keep them in this position making possible the most efficient operation of lower muscles, the true motors of breathing.”27 There is some validity to this; the majority of the expiratory muscles (discussed in a later section) are beneath the ribs in the abdomen, so they cannot control the air that is gained from costal breathing. If not being able to control the air is one of the primary reasons that clavicular breathing is inadvisable, it stands to reason that costal breathing should be discouraged as well. Unlike clavicular breathing, however, costal breathing does allow for control of exhalation through the interaction between the external and internal intercostals.

One can thus safely follow David’s costo-abdominal breathing without sacrificing singing quality.

Before moving on to the anatomy and process of exhalation, it is important to touch on a few miscellaneous points about inhalation. First, it is important to note that inhalation should be a silent process. Noise during the inspiratory process may be a sign of issues that will seriously affect singing. Most often, a noisy inhalation is a sign of a lowered soft palate, a too-narrow mouth opening, or a partial blocking of the airway by the tongue resting too far back.28 These issues ought to be resolved for a good breath and a good tone.

Second, while the process of inhalation involves a great number of moving parts, the whole process itself should be quick. Singers are often required in repertoire to inhale enough to get through fairly long phrases, in the space of a fraction of a second. Thus, while it is crucial to teach students how to breathe most effectively, it is also important to help them learn to do all this in short lengths of time. The third point makes drawing quick breaths easier, but it is important in isolation as well: one must not inhale too much. As Davids and LaTour note,

Singers should take a full breath because a relatively high lung volume helps to maintain a low larynx position, which in turn may help to reduce mechanical stress on the thyroarytenoids … At the same time, avoid the temptation to take as much breath as possible.29

Particularly when approaching long phrases, it will be the instinct of a young singer to fill the lungs completely in order to get through the full phrase. This is counterproductive. Richard Miller argues that by doing this, the lungs are so full to bursting that it will result in an unavoidably higher rate of exhalation. This means that the singer is less likely to sing through the full phrase than if they had taken a breath that was full, but not over-full.30 Finding this balance will take time, as one is not accustomed to taking deep, full breaths in their everyday life. However, as a singer becomes more familiar with their own voice and body, and as they learn how much breath is needed to sing a phrase of any given length, they will become more accustomed to the feeling of an appropriately full breath.

A good inhalation is important to the process of breathing. Such an inhalation relies both on a good costo-abdominal breath, which expands the abdomen and spreads the ribs. One must not, however, engage in the inefficient and harmful clavicular breath, nor should one inhale noisily. One must take a full breath, but not too full a breath, else they risk a too-rapid exhalation.

The Anatomy of Exhalation

Finally, we arrive at the final component process of breathing. In the typical functioning of the human body, air is exhaled once the cardiovascular system has reached a point of diminishing returns in gathering oxygen from the air in the lungs and replacing it with carbon dioxide. At this point, the expiratory muscles bring the lungs back to the position in which they began inhalation. Because the volume of the lungs is significantly decreased from this process, Boyle’s Law works in the inverse way as it did for inspiration. The air pressure within the lungs becomes much higher than the air pressure of the atmosphere, leading air to escape the lungs to maintain equilibrium between the two areas. The primary muscles used to achieve this action are more numerous than those used in inspiration, though, like inspiration, there are more muscles which are less involved. These muscles are the internal intercostals, the external and internal obliques, the rectus abdominis, and the transverse abdominis. The internal intercostals may be paired with the inspiratory external intercostals. They lie in the same place as the external intercostals, though the fibers of the internal move in the opposite direction than the external. Instead of pulling the ribs apart, as the external intercostals do, the internal intercostals bring them together, collapsing the ribcage.31 The external obliques run from the fifth rib down to the top of the pelvis, with muscle fibers that run the same direction as the external intercostals.32 The internal obliques have a similar relationship with the external obliques as the internal intercostals have with the external intercostals, running mostly perpendicular to their external counterparts. One way in which the two oblique muscle pairs differ is that the internal obliques run from the pelvis only up to the last rib, wrapping from the spine to the side of the abdomen.33 The rectus abdominis is separated into four sets of muscles going from the middle of the rib cage down into the pelvis, reflected across the centerline of the body to make a total of eight. These rectus abdominis muscles are at the very front of the abdomen, with muscle fibers running perpendicular to the floor.34 Finally, the transverse abdominis sits in the front of the body, wrapping around to the sides, and goes from the sternum down to the pelvis, with muscle fibers running almost perpendicular to the rectus abdominis.35 Because the primary expiratory muscles are more numerous than the primary inspiratory muscles, the work done by each individual muscle is less defined. However, as a whole, the muscles contract the abdomen and rib cage in order to return it to the position in which they sat before the inspiration.36 With this understanding of the expiratory anatomy, one may begin to understand the way the expiratory process differs in singing than in normal bodily operation.

The Process of Expiration

When one exhales in typical bodily function,37 the primary goal of exhalation is to evacuate the lungs in a relaxed manner, so when more oxygen is needed, the lungs can fill up in inspiration in the same relaxed manner as is typical (though the relaxedness of this process may be subject to the level of physical exertion). However, when singing, the objective is very different. The breath is the system which propels the vocal folds to make sound, and as such, the breath must be controlled to use it most efficiently. The amount of air required to move the folds efficiently and most effectively is quite small relative to the amount of air expelled at once in typical expiration. As such, one needs a system by which to slow the amount of air leaving the body during singing.

There are a variety of systems to manage exhalation. Miller lists several, including the “down and out” method, which encourages a focus on distending the abdomen outward. One may perhaps equate this to a preference for the action of the inspiratory muscles. There is also the “up and in” method, which encourages bringing the abdomen inward, accelerating the action of the expiratory muscles.38

These systems each have flaws. The “down and out” method places far too much emphasis on the distention of the abdomen. In the process of maintaining this distention, the singer may be encouraged to relax their good posture in favour of the distention, which harms the breathing process as a whole. The “up and in” method encourages a faster expiration than is needed or optimal for good singing. This leads to an aspirate phonation, or a phonation in which too much breath is used. The expiratory system which seems to be most prevalent in the literature is what is known as the appoggio method.

As James Stark notes, the root word of appoggio, “appoggiare,” is an Italian term which means “to lean.” Stark argues that this means two different things: first is the leaning of the breath on the larynx, through which the glottis (a piece of cartilage just above the vocal folds) slows the expulsion of the air.39 There is a limit to the amount of air that can be expelled during the open phase of the vocal fold oscillation. Provided there is a firm closure to begin with, this “leaning” will limit the amount of air leaving the body. The second component of appoggio is the leaning of the expiratory muscles on the inspiratory ones. Stark notes that this is often described as “a feeling of ‘bearing down’ with the diaphragm.”40 Given the complexity and difficulty of feeling the use of a single muscle, it is difficult to scientifically justify the feeling Stark describes. But the point is well understood. Rather than completely release the inspiratory muscles from all activity, the singer must continue to engage these muscles in the process of singing in order to slow the speed of the exhalation. Many authors, including Vennard and Miller, refer to this as “muscular antagonism.” This term, while more narrow than appoggio, is perhaps more descriptive and more useful in explaining the “muscular antagonism” aspect of the historical appoggio. The muscular antagonism is also the element which will conclude this discussion of breathing.

How may one achieve this muscular antagonism? Unsurprisingly, there are a variety of opinions on this subject. No one way to think about this subject is perhaps the “best,” but instead, one may benefit from borrowing from each of them. Vennard offers that one may feel the muscular antagonism as a feeling of “sitting on the breath.”41 Naturally, this must not be taken literally. The breath is not solid enough a thing upon which one can sit. Instead, one may interpret this to mean that one may settle into the sensation of the inspiration. It may help to gain comfort with this sensation by doing as Davids and LaTour suggest and engaging in a brief suspension of the breath.42 The sensation of active inhalation is somewhat different from the sensation of keeping these same muscles activated for muscular antagonism. By suspending the breath, a student may become accustomed to the sensation of maintaining muscular action of the inspiratory muscles during exhalation. This suspension is one of the aspects of the famous Farinelli exercises, in which a singer inhales, holds the breath, then exhales for gradually increasing counts – though Davids and LaTour seem to suggest a suspension much more brief than Farinelli. Davids and LaTour also caution that during such suspension, one must keep an open glottis. If one closes the glottis during this suspension of breath, it may encourage a hard glottal onset and therefore a pressed phonation, which is suboptimal. Miller notes that in order to maintain a good muscular antagonism, one must also maintain a good posture. Specifically, Miller highlights relaxed shoulders and a noble sternum, without which one cannot successfully maintain muscular antagonism.43 This is due to poor posture giving the ribs and abdomen less space to expand, which in turn harms the inspiratory muscles’ ability to fully engage, making it difficult for them to continue staying engaged throughout expiration.

Conclusion

Finally, one has a full picture of the process of breathing for singing. It begins with a good posture, continues through a full, but not over-full, costal-abdominal breath, and ends with an expiration that takes advantage of muscular antagonism to release the air at a controlled rate that is substantially lower than the rate typical of bodily function. With a mechanism so complex as the human body, it is little wonder that there is such a variety of opinions on the subject of breathing – especially in something so unnatural as classical singing. If the pedagogues have taught anything, it is, first and foremost, that Tennyson was wrong in his assessment: There is nothing dull about breathing.