Long before Astrid S. Tuminez became a college graduate — long before she lived in

New York City and the Soviet Union and Hong Kong and Singapore, before she published

a book and many articles and helped broker peace negotiations and held leadership

positions at universities and corporations, and before she was chosen as Utah Valley

University’s seventh president — she learned to dream.

From a tiny hut on the beach in the Philippine city of Iloilo, through holes in the

grass roof that always needed patching and from which water poured during rainy weather,

sending her scrambling for the shelter of the family table, Tuminez could look up

and see the stars. For her, she says, the stars symbolized dreams. And dreams were

free.

“I realized no matter how poor you are, you could actually dream,” she says. “Nobody

can stop you from dreaming about where you want to be, and what you want to do with

your life.”

If that sounds unrealistic, you haven’t met Astrid Tuminez. Her life is a flourishing

example of the power of dreams — and the role education plays in achieving them. As

she begins her service as UVU president this September, her goal is to pass on that

transformative power to all the people that she can reach.

“To believe in what is possible, whatever the hurdles and challenges are — that’s

the culture I’d like UVU to have,” Tuminez says.

Astrid Tuminez was the sixth of seven children born to Redencion Segovia and Lazaro

Terre Tuminez, in a village called Pali in the Philippine province of Iloilo, an hour

south of Manila by air. When Astrid was two years old, the family moved to the city

in search of better educational opportunities. After helping a local politician win

an election, her mother received a land allocation in a squatter area by the sea.

There, the family built a hut from bamboo and nipa grass, suspended on bamboo posts

above the ocean.

While neither parent was formally educated beyond high school, Tuminez describes them

both as intelligent and curious — “They had opinions about everything,” she says —

and singles out her mother in particular as inventive, creative, and resilient.

“My mother was the one with the ambition to move us to the city,” Tuminez says, “even

though we had to live in the slums. She knew that her children’s future would be in

the urban area. My father was more relaxed about the future. He was the kind of person

who could be quite content to just sit under a coconut tree and dream.”

Her father showed Tuminez the art of equanimity along with positive thinking. He could

be unruffled even under the worst circumstances. When her baby sister suffered a high

fever for several days, and they had no means to take her to the doctor, Tuminez and

her siblings feared the worst. But her father reassured them.

“My father sat on the balcony of our hut, told us we should all be calm, and that

whatever will happen will happen,” Tuminez says. “I thought, ‘Wow, how can he think

like that?’ But there's also a certain strength to that. That was my father. He was

a gentle soul, and I loved that about him.”

Tuminez inherited her mother’s inventiveness and her father’s positivity. Both served

her well in the slums of Iloilo, where the problems created by poverty required practical

solutions. For example, Tuminez describes stuffing her tattered shoes with lollipop

wrappers, because the waxy paper seemed better at plugging the holes and keeping water

out.

“When you are poor, you learn to be very inventive even as a child,” she says. “You

really learn to be a problem solver because you just can't sit there and buy your

way through your problems.”

One problem the family couldn’t solve on their own, though, was access to education.

For that, they had to rely on what Tuminez describes as “a miracle” — a chance encounter

with a group of Catholic nuns belonging to the Daughters of Charity, a religious community

that traces its roots to mid-17th-century France. While on a visit to the slums to

donate food and clothing, one of the nuns, Sister Elvira Correa, became particularly

impressed by how well-spoken and intelligent the children were. She offered Astrid

and her sisters the chance of a lifetime.

The nuns gave Tuminez a solid foundation in values. “I remember one young nun who

told me one day, ‘Astrid, God is in every person,’” Tuminez says. “And I thought that

was such a profound, amazing statement, and it made such an impression on me. They

saw God in me and my sisters and my mother. And I had to do the same: see God in every

person I encountered.”

The Daughters of Charity ran a local school, Colegio del Sagrado Corazon de Jesus,

which normally would have been prohibitively expensive for the Tuminez family. But

the school had just started a new program for underprivileged children to attend tuition-free.

Tuminez was a perfect candidate. So at the age of five, with no prior schooling, she

took the first step in an educational journey that would take her around the globe.

Tuminez’s lack of preparation became immediately apparent on her first day at her

new school: she didn’t know how to spell her name.

“We wrote down A-S-T-R-E-D,” she says. “I had no idea.”

Next came the classroom seating, arranged with the smartest student in the first seat,

first row, and ending with the least competent student in the last seat, last row.

Tuminez was placed in the last seat, last row. And on her first few assignments, she

received a grade of zero — which she didn’t know was bad.

“I kept getting a zero on all these quizzes, and I thought that was a really great

grade,” Tuminez says. “I’d run flying home to my hut, telling my father, ‘Hey, look

at this wonderful grade!’ He never told me a zero was a very bad grade.”

Soon, however, she began to catch up, and the shame-inducing seating chart awoke a

competitiveness in her. Within a few months, she was reading and writing. A few months

after that, she earned the first seat in the first row — head of the class. And by

the end of her first year, she was allowed to skip first grade and move straight into

second.

Later, when the school integrated the children from its free program with the rest

of the students, Tuminez continued pushing herself. While other children spent their

recess playing and buying roasted peanuts and Coca-Cola from vendors in the cafeteria,

Tuminez hid in the library, reading every book, shelf by shelf, left to right.

Classmate Roberto Villanueva, now a successful doctor, lawyer, and professor himself,

recalls Tuminez as “a skinny kid with a faded uniform, and her hair was tied with

a rubber band, like a fountain or a spring. She wasn’t really the silent type — she

was brilliant back then.”

Her achievements gave Tuminez a sense of pride and accomplishment she hadn’t thought

possible.

“I think every child wants to feel validated, and every child wants to feel that they're

good at something,” Tuminez says. “In the Philippines, if you grow up on a lower rung

in the socio-economic ladder, you end up being almost invisible. Your life means almost

nothing. To be able to say that I could beat the richer girls — the girls who came

from rich families with cars and maids — it was an amazing boost to my identity and

to my confidence, and to my ability to believe that I could be so much more than what

I thought I was."

As Tuminez continued through high school, she still wasn’t sure what she wanted to

do with her life. Learning in itself was a powerful motivator, but she lacked the

role models in her life to show her a career path.

“I reflected on what I would do with my life, and realized I had to continue my education

because, at that point in time, the value of education was already very, very clear

to me,” she says. “Education also became the foundation of my own personality because

it was the one thing I was good at. To be poor but to know you're good at something

is wonderful; it gives you a lot of self-esteem and courage to keep moving.”

From her reading, Tuminez learned of a place called New York City, and by age 10,

she made a goal to live there. Around that time, her family also met missionaries

from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Astrid first heard of a

place called Utah. By age 15, she had finished high school and was studying at the

University of the Philippines in Manila, on a full government scholarship, but she

dreamed of emigrating to America and attending Brigham Young University.

She was accepted to BYU and, in November 1982 — at 18 years old, wearing a faux silk

blouse and a self-described “big, poofy perm” — Astrid Tuminez first set foot on American

soil.

“My point of entry was California. My sister’s husband, who was in the Air Force,

picked me up,” Tuminez says, “and as we drove on the highway, I first saw the arches

of McDonald's, and I got so excited and wanted them to stop. They told me it was nothing

special, but I was so thrilled to be in America.”

At the University of the Philippines, Tuminez began and then dropped majors in chemical

engineering and pre-med. (Any notion of becoming a doctor ended swiftly when a teacher

asked class members to catch, kill, and dissect a cat as a class assignment, she says.)

At BYU, she discovered an aptitude for languages, especially Russian, and chose to

double major in Russian literature and international relations. Both would come to

define her future career.

“I was in the first batch of BYU students that went to Moscow to study Russian, led

by Prof. Gary Browning, who has been a lifetime mentor to me,” Tuminez says.

By her senior year at BYU, Tuminez was already looking forward to graduate school.

She applied to three: Harvard, Georgetown, and Yale. All three accepted her, but Harvard

offered a full-ride scholarship. So she headed east, and at a church gathering near

campus, she met a young Harvard undergrad, Jeffrey Stuart Tolk. Reports differ as

to who noticed whom first, but the two hit it off.

“In my mind, the first time I met her was at a dance,” Tolk says. “I saw her dancing,

and she was beautiful, and a good dancer. Just a sparkly, witty personality. I was

pretty much smitten.”

The following summer, Tuminez was working in Europe for Harvard’s Let’s Go budget

travel guide and staying with a friend’s parents in Paris, when she got an unexpected

phone call on her birthday. It was Tolk.

“I was like, ‘How did you get this phone number?’” Tuminez says. “Jeff was working

for Senator Al Gore, and it was before the days of the internet. He'd gone to the

Library of Congress, found a Paris phone book, and looked up the last name of the

people I was staying with. That was the moment I decided I was going to date him because,

if he could find me in Paris on my birthday, then he was definitely dating material.”

To believe in what is possible, whatever the hurdles and challenges are — that’s the culture I’d like UVU to have.

Tolk and Tuminez married on June 13, 1988, just two days after Tuminez completed a

master’s degree in Soviet Studies at Harvard. Tolk finished Harvard Law School and

began work as a legal clerk for the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, while Tuminez

worked on her doctorate in political science at MIT. Over the next several years,

the couple juggled jobs — some requiring long-distance travel — and education, as

well as discussions on when to start having children. Tuminez was intimidated by the

idea.

“To be very honest, I could never see myself as a mom,” she says. “I just couldn't

see myself being pregnant. That just seemed so alien. And raising children was just…how

do you do that? I couldn’t do that. I felt that I was not qualified to do that at

all.”

While both parents were working full-time and Tuminez was trying to finish her doctorate,

Tuminez found out she was pregnant. Her new challenges, she says, were the best thing

that could have happened.

“I wanted to have that doctoral degree before I delivered the baby,” Tuminez says.

“It just fired me up. It was probably my most productive time in life. When I first

found out I was pregnant, I was just falling apart. I thought I could handle anything

but having a child. But that's because I didn’t know what I was capable of doing.”

The experience, Tuminez says, taught her the full potential that women possess. She

and Tolk would go on to have three children total, all while both parents worked full-time.

“It made me realize, ‘Wow, women can do this?’” she says. “Because I was doing three

things: working full-time in New York City, writing the dissertation at night and

on weekends, and dealing with a pregnancy. For the first time in my life, I actually

understood the strength of women at a very granular level. Because to work was nothing

for me. To study was not much. But adding a pregnancy and delivering a baby, and still

continue everything else—to me, that was an amazing discovery.”

The support of her husband was key, Tuminez says — both had to make sacrifices for

each other to achieve their goals.

“I don't think I would have done as well as I've done without Jeff,” she says. “When

people ask me, ‘How did you do all this? How did you have three kids and still carry

on a very demanding professional life?’ I always say, without hesitation, that my

husband is fully integral to that success. It's a partnership.

“When we were dating, Jeff said to me, ‘You're responsible for your own happiness,’

and that just stuck so well in my head. I wasn't marrying a man so that he could be

responsible for my happiness. That's a really, really important message. Jeff respects

and honors all of my dreams and aspirations, and, in fact, no one is prouder of me.”

Work took Tuminez around the world over the next two decades. Most of that time was

spent in New York City, fulfilling her childhood dream of living in Manhattan. In

the early ‘90s, however, Tuminez was working for Harvard in Moscow, putting her Soviet

expertise to good use. Tuminez describes her relationship with Tolk as a “commuter

marriage.” Without email or the Internet, communication meant transatlantic phone

calls, usually in the middle of the night for one person or the other.

By 1992, Tuminez moved back to New York full time, where the couple would both work

for the next 13 years. Tuminez served in positions with the Carnegie Corporation of

New York, as a research associate and program officer, and with AIG Global Investments

as a research director.

Both Tuminez and Tolk were working in lower Manhattan on September 11, 2001, a harrowing

experience for both of them. Tolk said he actually had a meeting scheduled in the

World Trade Center for that afternoon. Tuminez, five months pregnant and also working

on Wall Street. at the time, was fortunate enough to have been picked up by a livery

driver shortly before the first tower fell. They drove to the Upper East Side, where

she picked up their daughter from school. Tolk had to walk home almost all the way.

“No phones would work,” Tolk says. “Landlines didn't work, cell phones didn't work,

so I couldn't contact Astrid, I couldn't contact my family, I couldn't contact anyone…It

was a very sobering moment.”

The family would eventually move further uptown, residing there until 2005, when Tolk

was offered a position with Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) in Hong

Kong.

After the birth of their second child, Tuminez thought she might take a one-year sabbatical.

But only two weeks after leaving her job on Wall Street, she was asked to serve as

a consultant to the U.S. Institute of Peace, which was involved in facilitating peace

negotiations between the government of the Philippines and the Moro Islamic Liberation

Front.

Having lived in New York for so many years, and lacking familiarity with the Muslim

areas of the southern Philippines, Tuminez struggled at first in her new role.

“When I first went in, I was very much in a New Yorker frame of mind,” Tuminez says.

“I was very formal and official—making appointments and sticking to official protocols,

and I fell flat on my face. It was just a huge failure at the beginning. One of the

Philippine officials told me the Muslims had sent a cable to Manila saying, ‘Who is

this woman and what planet is she from?’”

Humbled, Tuminez had to start from scratch, seeking to earn the people’s trust by

listening to them and learning their history. She also led a program to bring in negotiators

from other parts of the world to learn their stories and how they dealt with and negotiated

grievances related to history, land, and identity.

“I came to discover a very important part of Filipino history and culture that I did

not know as a Christian Filipino,” Tuminez says, “and to this day I'm deeply appreciative

of what I learned about listening to people, why they're hurting, and why they're

fighting. I learned that conflicts are rarely, if ever, a clear division of the good

people and the bad people — there are so many variables that create violent situations.”

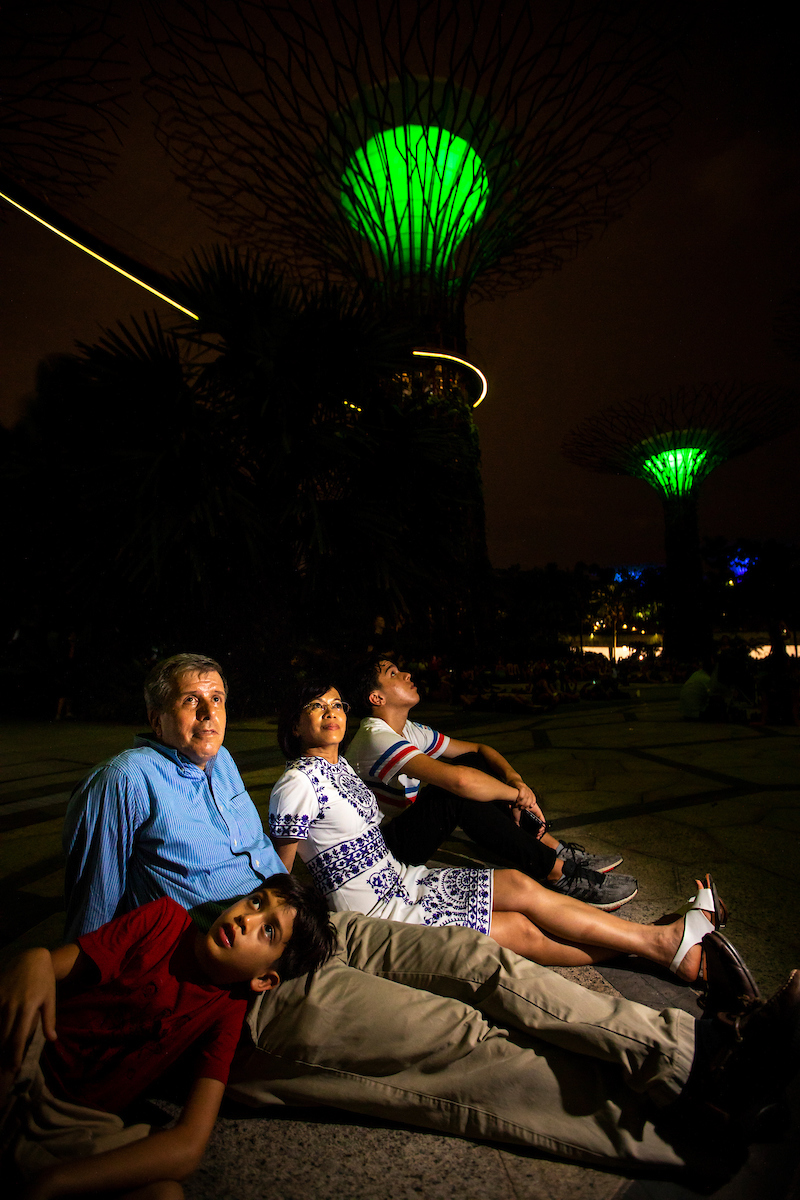

In 2008, Tolk accepted a job in Singapore, and Tuminez was considering an offer to

join a big tech company at the same time. But a meeting with Kishore Mahbubani, the

founding dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University

of Singapore, drew her back to her first love: education.

“Within 15 minutes of meeting me, he said, ‘What would it take to get you to work

for this school? You could be faculty, you could be an administrator, you could be

anything,’” Tuminez says. “I was so impressed by that, that someone could spot me

as a talent for the institution and could make up his mind so quickly.”

Tuminez held several positions at the LKY School, where she taught more than 2,000

government and business leaders and served as assistant dean of executive education

and vice dean of research. As vice dean, she helped support faculty in getting funding

and disseminating their research results. While at the LKY School, she also founded

a publication called Global-Is-Asian (a play on “globalization”), to help advance

public policy discourse in Asia.

“That was really a very wonderful four years,” Tuminez says. “It was a great way to

get to know Singapore, as a public policy lab in particular, and also get to know

the rest of the emerging markets in the region.”

“Dr. Tuminez is not only an academic, or just a simple adviser,” says Vu Minh Khuong,

an associate professor at the LKY School and a Harvard Ph.D. “She easily stands out

in terms of vision, in terms of ideas, and in terms of energy to push things through.

Rather than just academic discussion, she is very action-oriented. That's a good thing.”

Tuminez left the LKY School in 2012 to join Microsoft in Singapore as regional director

of corporate, external, and legal affairs for Southeast Asia. In that role, her team

supported 15 countries, driving government affairs, policy and regulatory engagements,

academic and nonprofit relations, and other activities to enhance understanding and

use of technology for the public good.

While she enjoyed her position at Microsoft, Tuminez was intrigued when a friend from

UVU informed her of the presidency opening. At first, she didn’t think the position

was right for her.

“I knew the university as UVSC, Utah Valley State College,” Tuminez says, “and I thought,

no, it's not a good match.”

But her curiosity led her to further research, and the more she read, the more intrigued

she became. Programs like UVU’s Center for National Security Studies, Center for the

Study of Ethics, Center for Constitutional Studies, and the 70-plus countries represented

in UVU’s student body, along with the institution’s integrated mission model, piqued

her interest.

“I became more and more intrigued, and more and more impressed,” she says. “Although

I had spent an enormous amount of time with elite institutions, whether that's Harvard,

MIT, or the National University of Singapore, I realized that UVU could be even more

dynamic and inventive in ways that would truly transform lives.”

“I did have doubts initially about the fit between me and UVU, but it occurred to

me that, if I could bring to one place my competencies and skills and my passion for

education, my passion for students, and my fundamental love and respect for professors

and what they do — this was the place to do it.”

With self-described trepidation, Tuminez submitted her application. She was selected

as one of four finalists on April 12, and, a week later, the Utah State Board of Regents

appointed her as the seventh president of Utah Valley University.

“Dr. Tuminez has proven to be a dynamic leader across academic, nonprofit, public

policy, and corporate sectors. Throughout her storied career, she has focused on bridging

gaps in education and opportunity to make a difference in people's lives, which seamlessly

aligns with UVU's institutional mission and core themes," said Daniel W. Campbell,

chair of the Board of Regents at the time. "Dr. Tuminez’s experience, vision, and

dedication to student success will ensure that UVU continues to thrive in the years

ahead."

Tuminez will officially start her presidency at UVU on September 17, and while the

Orem campus is a long way from that nipa hut in the Philippines, she already knows

what she wants UVU to feel like: a home, for every student.

“Home is a place where I feel supported, safe, and accepted,” she says. “Home is also

a place where I can articulate my dreams, and feel that I have the support to make

those dreams come true. Finally, home to me is always an unforgettable place. To every

freshman, and every parent, and all of the students and others in our community today,

I hope that you come to UVU feeling that this is your home.”