A Utah Valley University program — part of UVU’s recently awarded UNESCO Chair — seeks to understand the extent of water contamination in some of the most vulnerable communities in South America.

In a remote hotel room near Lima, Peru, Dr. Lauren Brooks worked through the night, hunched over buckets and sterilization tablets, testing water samples she had collected earlier that day. A biologist from Utah Valley University (UVU), Brooks had converted her shower into a lab, using the limited resources available to investigate a question that now had urgent implications: Was the water used by children and families in this region safe?

It wasn’t.

Despite using multiple sterilization tablets, the water she used to clean her instruments remained contaminated with human fecal matter. “Even after rigorous sanitation, the water was still unsafe,” said Brooks. “And this is water people are using to cook, clean, and drink every day.”

Brooks is one of several UVU faculty leading a major water-testing initiative in Peru. The program — part of UVU’s recently awarded UNESCO Chair — seeks to understand the extent of water contamination in some of the most vulnerable communities in South America. But while the UNESCO Chair provides the framework, the real story is what’s unfolding on the ground in Peru, where faculty, students, and government leaders are collaborating to uncover invisible threats and spark tangible change.

The origins of the project are as improbable as they are inspiring.

In 2024, Dr. Baldomero Lago, UVU’s chief international officer and now head of the university’s UNESCO Chair, was invited to meet with Peruvian congressional leaders visiting Utah. He presented on UVU’s work with Utah Lake, highlighting research on pollution and water sustainability.

During that meeting, he floated an idea: What if similar environmental issues existed in Peru’s lakes and water systems? What if UVU partnered with Peruvian institutions to find out?

Initially, there was little response from the universities in Peru. But one person listened — Dr. Lida Asensios Trujillo, president of the Asociación de Universidades del Perú (ASUP), which oversees 98 public and private university presidents across the country. Trujillo, who had accompanied the president of the Peruvian Congress to Utah, suggested focusing not just on lakes but also on the municipal water systems near Lima, where population density is highest.

She pledged her full support. It was a turning point.

Dr. Lago and Dr. Trujillo soon enlisted the cooperation of faculty, mayors, and university leaders across the country. The collaboration expanded quickly, and within weeks, presidents from four additional Peruvian universities joined the initiative. They represented regions as diverse as Chimbote, Trujillo, Chosica, and Puno, home to the iconic Lake Titicaca.

The scope of the study grew, eventually encompassing five focus areas: trace metals, microplastics, microbiology (including fecal contamination), algae blooms, and algae harvesting. By March 2025, UVU faculty and Peruvian faculty were on the ground in Peru collecting samples from rivers, lakes, streams, wells, and household taps.

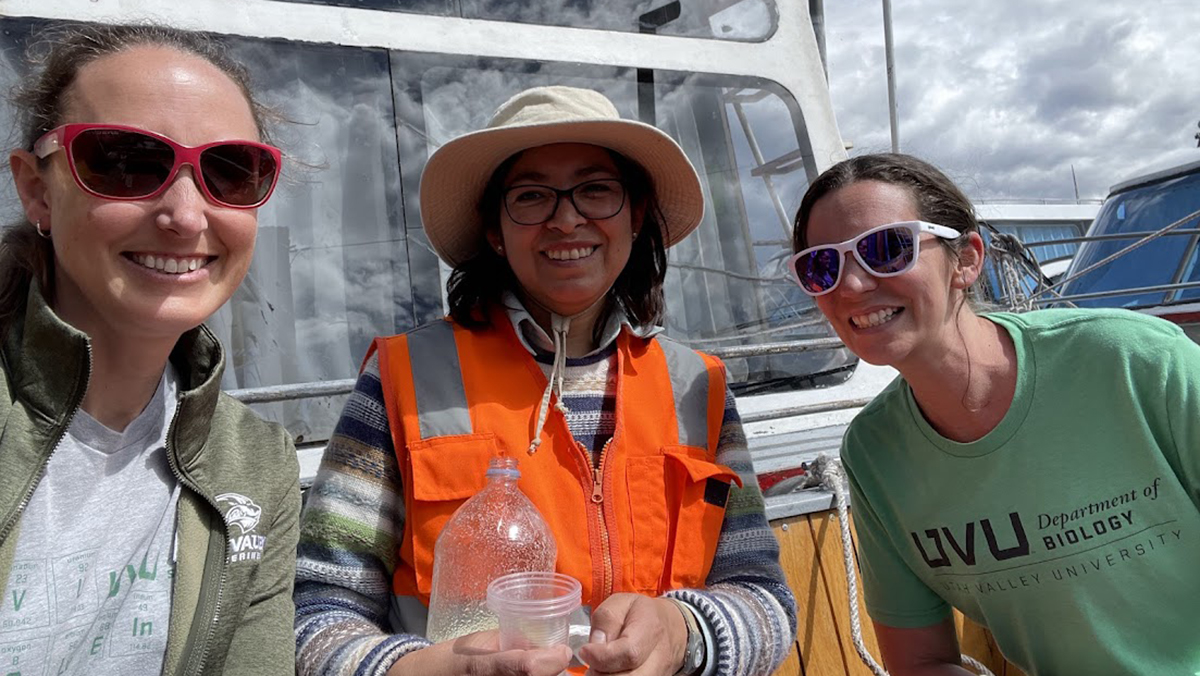

The effort is driven by an interdisciplinary team from UVU’s College of Science. Faculty members volunteered their time and expertise for the Peru study.

Over a six-day period in March 2025, the team collected 120 water samples across five municipalities. Each sample takes approximately 10 hours to fully analyze, a process now being supported by UVU students back in Utah.

“We want students involved, because this is real life,” said Dr. Lago. “At UVU, we call it engaged learning. We want students solving real-world problems to prepare them for the workforce and for global citizenship.”

The implications of the team’s work are sobering. In some communities, like Santa Eulalia outside Lima, school administrators report that up to 60% of students suffer regular digestive issues. “Most of them are sick,” a local principal told Dr. Lago. “Clean water would change the entire dynamic.”

The findings confirm what many local leaders suspected but couldn’t yet prove: their communities are being poisoned. Trace metals, arsenic, microplastics, and bacteria are widespread in water sources used daily for drinking, cooking, and bathing.

In northwest Peru, cities like Chimbote and Puno — both heavily involved in commercial fishing — are facing a double threat. Not only is the water contaminated but so are the fish that people consume. UVU researchers confirmed that both farmed and wild freshwater fish contained toxic elements.

One of the most significant culprits behind the contamination is mining — both formal and informal operations that dominate the Peruvian economy. Many of these activities are poorly regulated and discharge dangerous chemicals into rivers like the Rímac, which flows through Lima.

While the science is clear, policy change is the long-term goal. UVU faculty and their Peruvian counterparts plan to present their findings to the Peruvian Congress in December 2025. They’ll also meet with mayors, university leaders, and community groups to discuss possible next steps.

“Our role is to present the evidence,” said Dr. Lago. “We don’t force implementation. We’re an academic institution. That is why people trust us.”

Among the solutions being discussed are community education programs, water treatment reforms, faculty training, and algae harvesting programs near Lake Titicaca. The irony is that many Peruvian universities already have high-end water testing equipment, often donated by mining companies, but lack the training to use it.

“Equipment without expertise is useless,” said Dr. Lago. “That’s where we come in.”

For UVU, this project reflects a broader mission: to use education, science, and international collaboration to solve real problems. The UNESCO Chair program provides a platform for such initiatives, with goals that align closely with the United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda — particularly goal six: ensuring access to clean water and sanitation for all.

“This is engaged learning on a global scale,” said Dr. Lago. “We’re helping communities understand the threats they face. We’re giving them the tools to advocate for change.”

And that change is desperately needed.

“Imagine a child growing up with digestive illness because the only water they’ve ever known is polluted,” Dr. Lago added. “Now, imagine what happens when that water becomes clean. Their health improves. They do better in school. They become more productive. The community prospers. It’s a domino effect.”

With their next visit to Peru just months away, UVU’s faculty and students are preparing to return, not only with answers but with hope. Their work in Peru is not just a scientific study; it’s a lifeline.