Students in UVU’s forensic science department learn how to solve puzzles with evidence

By Barbara Christiansen | Photography by

Chelsea Gipson moved to Utah to study forensic science at Utah Valley University, in part, she says, to help “put away the bad guys.”

“Evidence doesn’t lie,” she says. “In my case there was physical evidence, but it wasn’t used correctly. In forensics, we are providing the facts. It also helps provide closure for others.”

Mentioning evidence and forensics can conjure up images of Sherlock Holmes with a magnifying glass, searching out clues. The field has evolved significantly since those days of fiction.

There are two parts to forensic science, and UVU — the only university in the state to offer a degree in forensic science — has incorporated both of those in its major. The program started out teaching students to take evidence obtained from a crime scene and analyze it in the laboratory. Courses included a lot of science, such as chemical analysis. The program has recently been modified to add a second track, with emphases on the investigative work done in the field.

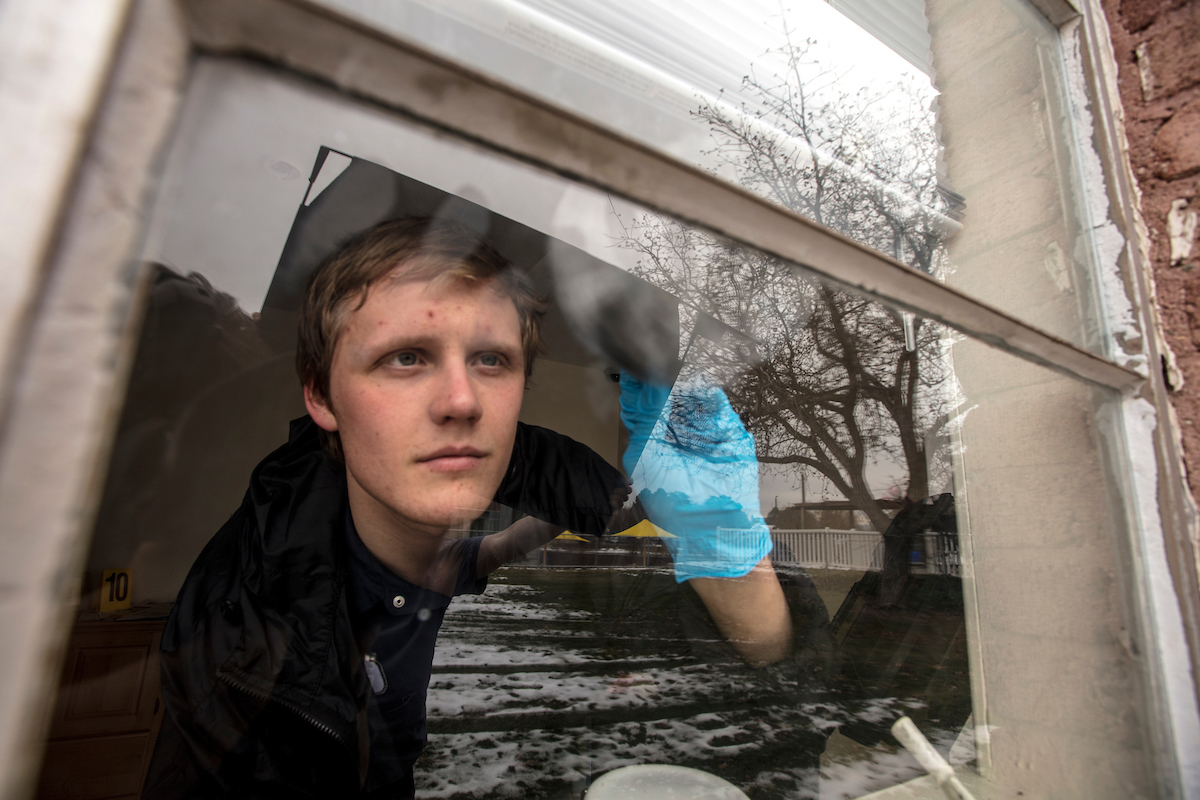

“The program provides access to state-of-the-art laboratory equipment, a practical crime scene facility, and professors with extensive backgrounds working in the forensic field,” says Amie Houghton, an assistant professor of forensic science. She handles the side that focuses on field work. One of those classes emphasizes crime scene processing.

“My class is made for mostly hands-on experience, not just theoretical knowledge,” she says. “My motto has always been, ‘You can be as book smart as you want in this field, but if you can’t put your knowledge to practical use, you will not succeed in your job.’ I have strived to make an engaged, real-life classroom experience.”

And she should know, having spent 11 years in the profession, working as a special agent at NCIS, the Naval Criminal Investigative Service.

She teaches her students, the majority of whom are women, to accurately document all aspects of a crime scene, including the trajectory of a bullet, the pattern of blood spatter, and exact locations of fingerprints. The students measure and record the information so it can be used in a court proceeding, if that becomes necessary.

In many cases it is easy to know what to document, but in others there is room for flexibility.

“Sometimes you use your gut feeling,” Gipson says. “A thing may feel out of place. You have to figure out whether something is normal or not. Each case is different. There is no one way to go about every case. You stand outside of the picture and decide what you need to look at, and what has been going on here.”

In the case of a death, until a medical examiner has made an official determination of the cause of death, the investigators document the evidence as if it were a homicide.

“People can try to manipulate the scene and make it appear like a suicide, for example,” Gipson says.

Carolyn Brown also majored in forensic science at UVU, with minors in chemistry and criminal justice. She graduated in December with a bachelor’s degree, and plans to go for a doctorate in forensic anthropology, which she anticipates will take another five years. In that field, she will analyze skeletal remains to determine characteristics about the deceased.

“Much of it is used for mass grave situations where they need to identify a lot of people,” she says.

“I grew up watching TV shows,” she says. “I looked into what a career in forensic science would entail. I started taking classes and fell in love with it. It is intriguing to be able to solve puzzles and problems. Forensics is doing that for a criminal mindset.”

The forensic investigator needs to do a rapid analysis of the surroundings of a crime scene, she says, since not all that is important is always readily visible.

When Brown first started the program, she was intrigued — but her interest continued to increase because of the teachers, she says. “They really helped me fall in love with forensic science. What I am grateful for in the program is that aspect. They really want you to succeed.”

In turn, Houghton loves teaching the skills. “I love when students come to love the classes and tell me they are glad we included them,” she says.

With that inclusion, they may find careers in the growing field as crime scene investigators, medicolegal death investigators, latent print examiners, impression evidence examiners, or firearms and ballistic evidence examiners.

They won’t need Sherlock’s magnifying glass. But they will be helping to put away the bad guys.