UVU administrators are on the lookout to speed up a student’s completion

By Jay Wamsley | Photos by Jay Drowns

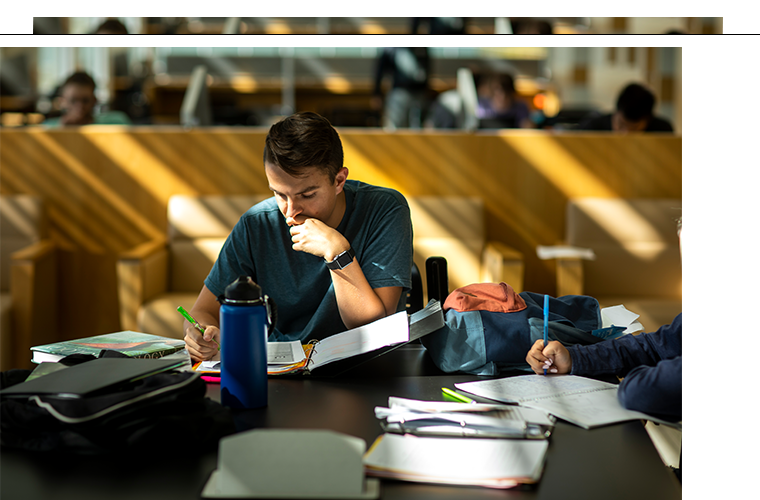

Barriers on a college campus usually mean detour signs, orange cones, or changes to a favorite parking lot. Utah Valley University administrators are looking for other specific barriers, bumps in the road that are keeping students from graduation.

In the short term, moving those barriers might mean getting financial aid easier or a new way to get a student ID. But long term, it could affect generations.

UVU has a 45% completion goal, meaning 45% of students will have an earned credential within eight years. This was one of the first benchmarks President Astrid S. Tuminez stated when assuming the top spot at UVU, echoing goals stated by the Utah System of Higher Education. Nationally, 60% of students enrolled in two- and four-year colleges in fall 2010 graduated in eight years; UVU’s rate was 36%, according to the National Student Clearinghouse.

“I think with putting the goal of 45% in place, it really caused all of us to be that more focused on what are the barriers, what are the conditions a student experiences that we can do something about,” says David Connelly, associate provost over academic programs. “We may not be able to find them a better job, we may not be able to simplify their home life or anything like that, but we can certainly get out of their way while they are here. I think it really helped us to focus our efforts and the barriers we can control.”

Among those listed by Connelly are smoothing the path toward applying for financial aid, getting schedules that work, and “getting more intrusive in talking to them about realities they are facing through predictive analytics.”

Andrew Stone, associate vice president for enrollment management, agrees. “In addition to big-ticket items like scheduling and paying for school, big things, we have removed barriers just by simplifying processes,” Stone says, noting improvements to MyUVU with dashboards that show a student his or her next step in the enrollment process. “We don’t want students to sit and wonder or wait for their next step — we want the process to be simple and accessible.”

Simplifying processes and eliminating barriers are especially important during a student’s first year, says Michelle Kearns, associate vice president for student success and retention.

“The first year is when the greatest risk for attrition occurs, and we’ve implemented quite a few things recently to help students succeed. Foremost would be our first-year advising center. The idea here is to provide a holistic, proactive, data-informed delivery of advising. That has been a significant investment by the institution to really help remove barriers related to advising during that first year.”

The new center, she says, increases access for new students and improves consistency in the experience that they have with an advisor. Another significant initiative is predictive analytics.

“The institution has invested in a predictive analytics platform that allows us to conduct timely interventions — nudges to students to take action and also encouragement to keep them on their path to completion,” Kearns says.

A third major barrier that is continually being examined and improved is core scheduling, Connelly says. With completion goals in mind, he said administrators are continually examining academic scheduling to make sure two required courses are not taught at the same time, on the same day, or that courses are being sequenced in a way that works for students, removing overlaps between the start times and finish times on classes. “It’s best that you can walk out of your class and 10 minutes later walk into your next class. We are trying to cluster the classes together as best we can.”

“We have to remember that 80% of our students work, along with all the other constraints that they have,” Connelly says, “so we are trying to help them get out to a full schedule, rather than only being able to one or two classes here and there, and, of course, the multiple trips that requires [them] to come to campus and all the other constraints with that.”

… It really caused all of us to be that more focused on what are the barriers, what

are the conditions a student experiences that we can do something about… We can certainly

get out of their way while they are here.

— David Connelly

The first year is when the greatest risk for attrition occurs and we've implemented

quite a few things recently to help students succeed.

— Michelle Kearns

Surveys, as well as practical observation, show that finances continue to be a significant barrier for students, Kearns says, describing two new scholarships that were announced early in 2020 to help students hit their graduation finish line. One, she says, is the UVU Greenlight program, which is a scholarship for first- and second-year students.

“And we just rolled out the new UVU Reach Scholarship,” she says, “which helps motivate students to reach critical completion milestones. When you talk about barriers to completion, finances are often at the top of the list — so the investment made in these two scholarship programs is significant.”

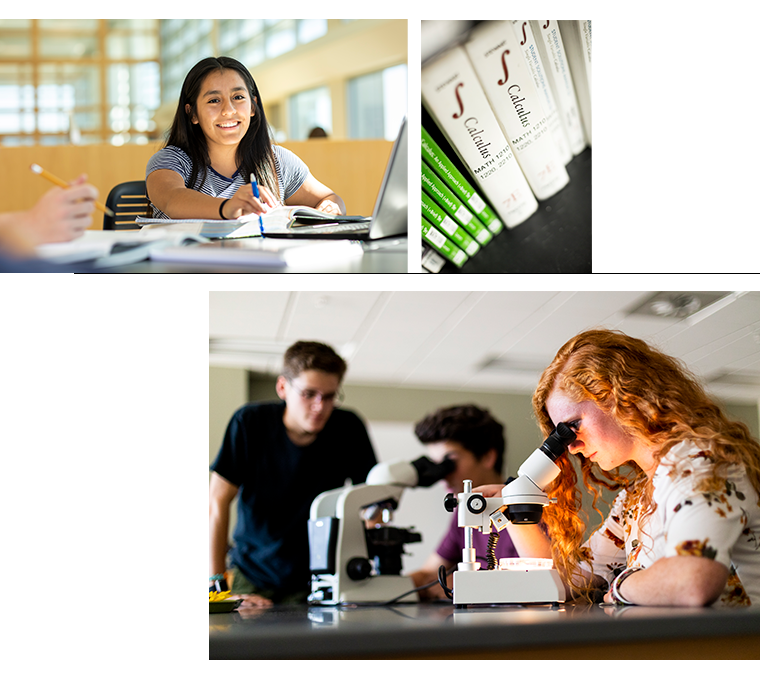

Identifying and removing barriers is not necessarily a new thing at UVU. More than a decade ago, when math classes were pointed out — by students and faculty alike — as a pinch point along the path to completion, the university started a developmental math program. At its core, the developmental math program aims to improve the pass rates of students who find math a major barrier to their continuance.

Ben Moulton, a professor in the developmental math program at UVU, says there is a movement nationally to strip away developmental programs — those that back up and infuse basic understanding for struggling students — thinking that it adds to their overall length of stay at college.

“Being an open-enrollment institution, we are fighting against that,” Moulton says. “If you do that, where are those students going to end up? You shouldn’t take away that element of the community college model. Let’s keep the dual mission that we have and help these students get through it.”

Moulton says the UVU developmental mathematics program heavily utilizes math mentors — fellow students who are able to teach and motivate those who find themselves math-challenged. These mentors, he says, also end up being friends and an important campus resource to newer students.

“Part of the math mentor program serves the purpose of the caring aspect. We are trained to care about the student; we are human beings serving as a resource to the student,” Moulton says. “We are trying to get them through the course the first time so they don’t have to repeat it, and if our mentors work with one student — hopefully it can be done with the whole class — they can pass the class that they wouldn’t have before and get on their way.

“Think how much a student pays to take a class a second time. Put a student mentor in there, and that money would have more than paid for that assistance. Cost aside, our mentors have helped improve pass rates by more than 10% in our department. Apply that to several thousand students per semester, and it’s a pretty significant number.”

Mentors sit with students in their math classes, not just providing out-of-class tutoring. Moulton says in-class mentors can see what the instructor is teaching, and that is helpful because when they meet with the student, the student knows what the teacher expects. “Not only that, but with anxiety and depression and some real things that a student can feel, our mentors can help them find resources,” he says. “Some of these students come to campus and they are terrified of college. They are terrified of many things and don’t even have any friends on campus, and so the mentor is there to be that friendly person.”

As many as 2,500 to 3,000 students go through the developmental math courses during an average fall semester.

Photo by Gabriel Mayberry

Is it possible to eliminate barriers — or at least make the path shorter and smoother — before even stepping on campus as a UVU student? As mentioned by Pres. Tuminez in her 2020 State of the University address, a sometimes-overlooked demographic of UVU’s growing student body is the concurrently enrolled high school student.

“This high school-university shared program has doubled in size over the last five years. Subsequently, the high school programs are outpacing the growth we are seeing here on campus,” says Spencer Childs, director of concurrent enrollment. “UVU has 41,000 students enrolled, but remember, 12,000 of those are concurrent enrollment students.”

Childs points out that state rules guide the activities surrounding concurrent enrollment programs at each of Utah’s postsecondary institutions. For example, UVU operates inside of a specific service area that has been predetermined by the state. The service area includes the four school districts in Utah County and Wasatch.

He said additional studies are presently underway to determine if concurrent enrollment students are completing their education in a more timely fashion — regardless of how many credits were earned in high school before arriving on campus — versus students who don’t participate in the program.

“Anecdotally, it makes sense that a student entering the university with college credits will have a higher rate of completion. Because of this, our vision is to make certain we include concurrent enrollment as part of their experience. By doing so,

students will start strong and flow right into the university,” Childs says. “We want to give them not only credit, but a college experience, and get them to understand the support systems that are here. We think that will be really beneficial.”

One of the main initiatives for the Concurrent Enrollment Office is to identify and serve underrepresented populations, Childs says, as the concurrent enrollment program is designed to be affordable and accessible to all.

“Being a first-generation student, you are already there at the high school and in a familiar classroom. It’s such a great way to introduce them to college in a way that is not intimidating.”

With the program now in its 32nd year, it is positioned to increase its reach and effort to better serve a broader demographic, he says.

When completion rates are examined, often they are only nudged up a single percentage point at a time, but up is the way they need to go, Connelly says. A 45% completion rate is attainable, he says, “and then we need to go past that.”

“While a 1% increase may not feel like a giant step forward in terms of things for our students,” he explains, “a 1% step forward for our students means 41 students, and it is important to them. One percent is 41 more students graduating, 41 more students getting the advancement that they need, which means 41 lives have been changed, which affects generation after generation.” ◼