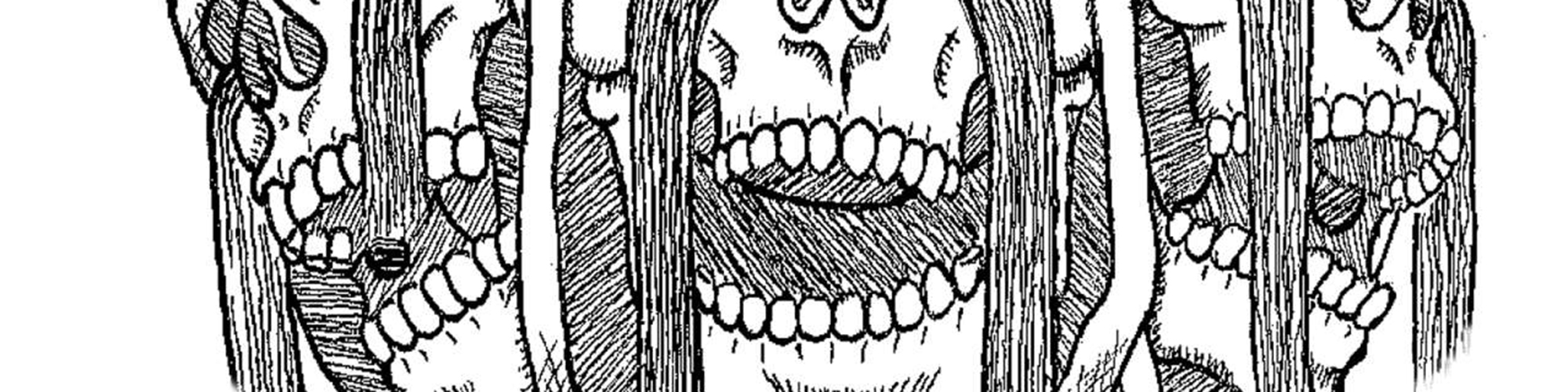

This is a portion of a larger piece I did that I wasn’t the biggest fan of, however, I liked this part of the work. It is the idea of three beings that watch over all. The emotions they feel are always on full display and here they cry for different reasons while looking at the same thing.

In academia, almost all of the scholars are trying to make sense of the “fake news” phenomena that has ravaged the internet. They are trying to define something that took off so quickly that they are still not sure exactly what it is. Even to this day, six years after the first real incidents of “fake news” started cropping up in the United States (the 2016 US election), experts are still scrambling to give it a proper definition and function. Yet simply defining “fake news” does not capture the scope of a government-backed disinformation campaign actively seeking to bend a population to their will. The United Nations needs to stop ignoring this problem and make disinformation punishable by more than just a simple fine.

Introduction

In academia, almost all of the scholars are trying to make sense of the “fake news” phenomena that has ravaged the internet. They are trying to define something that took off so quickly that they are still not sure exactly what it is. Even to this day, six years after the first real incidents of “fake news” started cropping up in the United States (the 2016 US election), experts are still scrambling to give it a proper definition and function. Yet simply defining “fake news” does not capture the scope of a government-backed disinformation campaign actively seeking to bend a population to their will. The United Nations needs to stop ignoring this problem and make disinformation punishable by more than just a simple fine.

Throughout this article, I will explore what is currently being focused on by scholars. After identifying what these scholars missed, I will give a definitive definition of the various terms that appear in the works of these scholars. Following the exploration and proper definitions of false information, I will show why we should be focusing on combating disinformation (rather than defining it) by providing various examples of modern disinformation. Finally, I will explore a possible solution to the problem. My hope is that I can convey a sense of urgency about the underlying problem with merely defining and simply talking about disinformation.

Defining False Information

Even though I just criticized most scholars for focusing on defining disinformation, it’s still worth talking about because this is where the conversation begins. To start, many scholars question why false information doesn’t lose its momentum not long after it begins. Toma and Scripcariu tackle this by suggesting that there are five different definitions that misinformation can fall into: “recurrent occurrences,’ ‘scapegoat offensives,’ ‘pseudoscientific gaze,’ ‘combo strikes,’ and ‘humorous hijacks.”1

I would like to add a sixth definition called “absurd scams,” which is an idea that is so out of left field that it unironically is more believable. I will refer back to this in a moment. Toma and Scripcariu define the five examples as misinformation, but I think a few of these could definitely be defined as disinformation as well; scapegoat offensives, pseudoscientific gaze, and humorous hijacks could all be taken to the extremes and end up as disinformation. Baptista and Gradim build on what Toma and Scripcariu said, saying that many scholars reject these definitions, that they are “unstable’…[and] ‘absurd’ [in] meaning.”2 They then propose their own definition of disinformation, stating that it is “…intentionally designed to mislead and/or manipulate a specific or imagined public.”3 In most of the definitions that these scholars provide, it is implied that a foreign party—whether a person, state, or company—from a position of power—usually a political rival—disseminates false information to deteriorate an opposing viewpoint, often with physical consequences. I think it’s safe to say that every scholar agrees that disinformation is bad; however, my concern is still “What should we do about it?”

I mentioned “absurd scams” as an addendum to Toma and Scripcariu’s five misinformation ecosystems a little earlier. The concept of “absurd scams” is based on Miller’s article, in which he briefly describes a few attempts by the Russians to frame the Ukrainian Government in a bad light: the supposed crucifixion of a child by the Ukrainian Government, ISIS training camps set up and approved by the Ukrainian government, and the printing of Hitler’s face on their currency.4 To be perfectly clear, the aforementioned examples are fake; they have been debunked by StopFake.org—a non-profit organization dedicated to exposing disinformation spread by Kremlin media outlets.5 These are examples of absurd scams because they are way out of left field, and yet, there are those who believed them—hook, line, and sinker. Bockett proves why disinformation is so effective through soft balancing, yet he seems to have shouted into a void; not one of the recent articles I’ve read has mentioned his paper.6 Perhaps this is because soft balancing is a term associated with traditional warfare and hasn’t quite made its way to online interactions yet. Regardless, disinformation is a problem that hasn’t been addressed properly, and most scholars have yet to suggest any effective countermeasures against it.

Disinformation, Misinformation, and Fake News: An Examination of Discrepancies in Definitions

In order to understand why we shouldn’t be focusing on defining false information anymore, I decided to analyze how these terms showed up in previous academic articles. There are three different terms that appear in various contexts: “fake news,” disinformation, and misinformation. These three terms, although having separate meanings, are used in a way that makes it confusing for the reader to understand. In hindsight, I can see that these terms are indeed different—and for the most part, used properly; however, before I had come up with my definition, that was not obvious to me. For example, in Aswad’s article, “misinformation” is never seen without “disinformation,” and the only exception to that is in the footnotes, but it’s easy to overlook because the footnotes take up the entire page.7 A second example is that of Toma and Scripcariu’s Misinformation Ecosystems: A Typology of Fake News, in which they use misinformation as a synonym for “fake news,” as well as occasionally throwing disinformation into the mix.8 Again, prior to coming up with my definition, this confused me quite a bit. These are only a few examples of confusing terminology. There are many more examples, but that would warrant an entirely different paper.

Having examined various discrepancies of disinformation, misinformation, and “fake news,” I will set forth my definitions of the various terms in a way that is not confusing, vague, or misleading. Beginning with “fake news” of the modern era, this can be defined as a popular term coined by the media; it represents false information on an online platform. To further cement this definition, Baptista and Gradim’s article A Working Definition of Fake News agrees with my definition, where they describe “fake news” as “a type of online disinformation.”9 They do define “fake news” as disinformation—which is fine; however, I would still argue that “fake news” is coined by popular media as a means to scare people. If any more explanation is needed, then suffice it to say that the definition that I provided will be enough for this article.

Following “fake news” is misinformation, which can be defined as false information that was unintentionally produced. In other words, somebody got their facts wrong. While this isn’t nearly as destructive as disinformation, misinformation can have a harmful impact. A prime example of misinformation is a story I heard from one of my high school English teachers on November 21, 2022. In this story, my teacher had a neighbor who happened to be on the sex offenders list. Once the rest of the neighborhood found out, they were determined to root out this dangerous person from their peaceful, sex offender-less community. At first, my teacher was a part of that group. After doing some digging, however, he found out that this person on the sex offenders list was only there because he had sex with his wife before they were married. After learning this, my teacher did his best to spread the truth—the truth that this person was not a criminal to be afraid of. His efforts were in vain, as the family moved away not long after. This story goes to show that getting facts wrong can have serious consequences. It can ruin reputations, upset relationships, or, as we saw in this story, displace people. Misinformation, however, is only the lesser of the two evils.

Finally, we have disinformation, which can be defined as false information that is intentionally and deliberately disseminated to alter the opinion/viewpoint of a certain demographic. There are many examples of this—the most recent of which is right on our home turf in Orem. According to the Daily Herald, an email was sent from the South West Orem Neighborhood Association announcing that “Alpine School District Announces Orem School Closures!”10 There was also an article published on KSL (and later removed) labeling eight schools for closure and demolition in Orem.11 Needless to say, these false articles are local examples of disinformation, and undoubtedly affected the results of 2022’s mid-term elections in Orem, Utah. These definitions go to show that although these terms can be used collaboratively, one should be careful how they employ them—lest they confuse their audience.

Russia and Disinformation

One does not simply bring up disinformation without mentioning Russia. In every article about “fake news,” disinformation, or misinformation that I’ve read, Russia is brought up at least once. In Toma and Scripcariu’s article, they bring up a Russian social media game from 2017—known simply as the “Blue Whale”—in which the game appeared to be threatening a huge population, but the reality was that the impact was small and rather insignificant.12 Although the article mentions that this occurred in Romania, this instance should not be casually thrown aside; it shows how much Russian influence affects everyone.13 Moving to more modern times and the current issue of Russia and Ukraine, Miller describes how Russia lies to the Russophones in Ukraine, creating fictitious stories to persuade them to abandon the “fascist” government and return to Russia.14 These efforts have been so effective, that the Donbass and Crimea regions of Ukraine “…came to support… separation from Ukraine or outright annexation by Russia.”15 Bockett confirms what Miller says, saying that this strategy—which he coins as “soft balancing”—has been “…much more effective…than traditional military…strategies.”16 This strategy is so effective, it caused Dawson and Innes to write an entire article on how the Russians handled their disinformation campaign, exploring the various methods of how the Internet Research Agency (IRA) influenced the various countries of the world.17 They gain notoriety on Twitter (and therefore, influence) through a combination of these three methods: buying followers, follower fishing, and narrative switching.18 All of this goes to show that the Russians have perfected the art of manipulation through false information—and not just propaganda in their home country.

Disinformation as Warfare

At the turn of the millennium, as the internet exploded in popularity, and the world became more interconnected, the ability to spy on, steal from, and attack other countries was becoming easier than ever. As Eun and Aßmann state, “cyber operations alone…have the potential to [become] international armed conflict.”19 They also argue that information, specifically online information, will become a fifth platform off of which to wage war.20 Although the focus of their article is on digital weapons that have kinetic consequences, their argument can also be applied to disinformation as well. Bockett elaborates on this through his concept of soft balancing—decreasing a rival’s power versus increasing one’s own power.21 Miller shows soft balancing in the Russo-Ukrainian War of 2022, in which Russia floods Ukrainian media with blatantly false information, and Ukraine fights back with memes—a sort of front-line defense for those on social media, piloted by the North Atlantic Fellas Organization, or NAFO.22 The examples above are only a few examples of how disinformation has been weaponized, and the list is only growing.

A Modern Conflict

Now that the dangers of disinformation have been revealed, I can continue on by showing how disinformation is affecting the world today. The first instances of disinformation that I can find were a result of the Euromaidan Revolution in 2014—a revolution in Ukraine caused by the refusal to join the EU. Prior to the Euromaidan, a Russian sympathizer occupied the president's chair, and the Russians spread their thoughts and ideas through various news channels—primarily social media.23 During and after the Euromaidan, Russian media outlets labeled the revolutionists as “fascists’ and ‘brutal Russophobic thugs.”24 The worst part? Those in the Donbass and Crimea regions believed this—hook, line, and sinker.25 In case it wasn’t obvious, these accusations are false; they were spread by the Russians in an attempt to bring Ukraine back under Russian control. Fast forward to 2016, the Russians have taken an interest in US politics.26 According to Time magazine, the Russians hacked into the Clinton campaign network, stole emails and passwords, and used it to produce negative news against Clinton, and that was only a small slice of what they did.27 According to Bauer and Hohenberg, the Denver Guardian—a false media outlet based on the Guardian—spread false information about Hillary Clinton that attracted hundreds of thousands of views, and undoubtedly altered the results of the election.28 In 2017, Russia decided to pull the strings in a second country—France. Had they succeeded, Marin Le Pen—the candidate that the Russians backed—would have removed France from the EU, likely creating political unrest throughout Europe.29 All of this goes to show that Russia is actively affecting global politics through disinformation, and, as far as I am aware, nobody has done anything about it.

These disinformation campaigns are not isolated to the past. They continue on today, right under the nose of the worst war seen in decades—the Russo-Ukrainian War. In the weeks leading up to the invasion of Ukraine, the Russians began saying the Ukrainian military was about to attack the Donetsk and Luhansk regions—both of which are inside Ukraine’s borders.30 A few days before the invasion, they created a video of the supposed shelling of a civilian town, in which the “citizen” lost a leg.31 As the war started, videos of the alleged “Ghost of Kyiv” were created by the Russians to spread false hope among Ukrainian supporters.32 Once again, disinformation is not a thing of the past. Disinformation is a vital tool in the Russian arsenal, and they are using it very liberally.

That’s not to say that Ukrainians aren’t fighting back. Ever since the Euromaidan, StopFake has been debunking Russian disinformation non-stop.33 In fact, they are still debunking disinformation to this day. They are not the only ones combatting the disinformation onslaught, however. An online community known as the North Atlantic Fellas Organization, or NAFO, has banded together to debunk the Russian disinformation on the front lines, so to speak. NAFO is known for creating memes that involve the popular Shiba Inu dog. This has gotten so large that Adam Taylor, a reporter for The Washington Post, wrote an entire article on NAFO.34 Spreading memes about Russian disinformation, however, won’t stop it from happening.

An Idea to Proactively Counter Disinformation

Although Russian disinformation is being constantly debunked, simply debunking disinformation isn’t enough. Something needs to be done that will prevent disinformation from affecting a population again. Unfortunately, there is no framework to go off of—simply because this form of disinformation is much newer and harder to identify. The closest thing I can find to a possible framework is the United Nation’s Atrocity Crimes—more specifically, the page on Crimes Against Humanity. Using these guidelines, I would argue that disinformation—especially when it is backed by the government—would fall under the persecution category, fulfilling the physical element of the crime.

Am I bending the definition of “persecution” to fit my needs? I don’t think so. Seeing as persecution is defined as hostility due to race, political or religious beliefs, I think Russian disinformation fits this definition rather well, if not perfectly. The physical element isn’t the only thing that needs to be considered, however. According to the UN, there needs to be a contextual and mental element considered in tandem with the physical element. The contextual element is defined as “…[a] part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population.”35 The Russian disinformation campaign is indeed a part of a greater whole; in case you weren’t aware, that greater whole is the war that’s been going on for almost a year now. Finally, the mental element requires that the attacker must have knowledge of the attack. I would argue that Putin is very aware of this, especially because he has a branch of his government dedicated to doing just that—the Internet Research Agency, or IRA.36 Therefore, with all three categories’ requirements met, I would argue that Vladimir Putin is indeed a war criminal and should be dealt with accordingly.

There are those that would see my solution as censorship—after all, I am arguing that disinformation should be, well, censored. These people have good reasons, too. After all, censorship laws are generally created to identify and eliminate those that are against a certain political regime. A prime example of this is an instance that occurred in Singapore in 2019. Although it was well-intentioned, a law banning “fake news” was used “…for the purpose of silencing a regime critic, rather than for the reasons originally cited…”37 As a counterpoint to the censorship law abuse, I would argue that censorship laws must be handled by an international court, a separate entity that (ideally) would have no biases and could examine the potential offenders with a clean slate. Finally, to quote Aswad once more, this does indeed involve “…an enumerated public interest objective…” seeing as there are lives on the line.38

Conclusion

Information—which was once thought to be useful only when it was tangible—has now been weaponized on a level never seen before. Information has become the fifth platform off of which to wage war (if it wasn’t already). Disinformation—which is deliberately disseminated false information—has been used to sway the opinions of those who would otherwise be an enemy, as seen with Russia and Ukraine. While StopFake and NAFO are helping fight this disinformation, they can’t do everything on their own. This is why I have argued so heavily for laws against international disinformation. Something needs to be done, and not just a slap on the wrist. The time to stop defining disinformation is long past us—that was way back in February of 2022. We need to start combating disinformation and curb this problem as soon as possible—not just for the benefit of Ukraine, but for the entire world.

This project is a component of my research aimed at extrapolating the boundaries of images depicting cancer cells. The code presented represents my initial efforts to construct the fundamental framework necessary for developing a more intricate architecture to accomplish this task. This marks my first completion and presentation of a neural network.

Colored pencil on paper. This piece represents how some people might worship the goddess of pumpkin spice lattes in their life. Are you governed by your need for coffee? Do you feel like coffee, or in this case a pumpkin spice latte, controls you? Take a step back and think about the things in your life that you “worship” or that you idolize.