The purpose of persuasive writing is to convince an audience to think, feel, or act in a specific way. Examples of persuasive writing include advertisements, opinion editorials, political speeches, argumentative essays, cover letters, grant or research proposals, and social media posts. This handout outlines suggestions for persuasive writing, but always write with your audience and assignment in mind.

Select a subject you are interested in to keep you engaged in the writing process. Make sure there is ample research available and multiple perspectives to examine and inform your work.

Purpose provides direction and intention for your writing. Determine if you are arguing for or against something and what specific action you want the audience to take as a result of your argument. Do you intend to inform, convince, inspire, motivate, or call to action?

Identifying your audience’s shared values, beliefs, and concerns is crucial for persuasion. Consider the size of your audience. Are you persuading an individual or a group? Understand your audience in relation to your position. Are members of your audience neutral, supportive, or opposed? Tailor your approach accordingly.

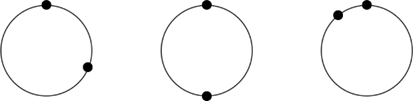

Your position in relation to that of your audience will inform how you communicate with and persuade them. Imagine your position as a point on a circle with your audience’s viewpoint also located somewhere on that same circle (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Points on circles to represent varying positionalities in relation to each other.

No matter your positionality, establish and frame your position, building upon shared values, beliefs, and concerns. For example, you and your audience may share a concern but have different ideas about addressing that concern. Alternatively, your stance may appear opposite from that of your audience, but you may have shared experiences or values to draw upon. Continually assess your position in relation to your audience, and adapt your approach to persuasive communication accordingly.

Researching and understanding other perspectives is helpful to establish credibility with your audience and strengthen your persuasive impact. Broadening the range of your research will help you become more informed, assist in identifying and navigating biases (preconceived beliefs and assumptions), and may lead you to a different or more nuanced perspective. This process will continually help you to narrow the scope of your subject and determine your stance.

Rhetorical appeals are methods of persuasion that help writers appeal to and build relationships with their audience. Key rhetorical appeals are ethos, pathos, and logos.

In persuasive writing, you will generally use a combination of rhetorical appeals to effectively persuade your audience to act or agree with you. Select rhetorical tools specific to your purpose, audience, genre, and discipline or field.

Outline your argument based on your claim, audience’s needs, and genre of writing. Most successful persuasive writing will include the following elements: